You can have your holly-jolly Christmas and your Auld Lang Syne. For me, the highlight of the season is Festivus, “the holiday for the rest of us,” introduced by the character Frank Costanza in a “Seinfeld” episode that originally aired on December 18, 1997.

Festivus has been described as “playful consumer resistance” and "the perfect secular theme for an all-inclusive December gathering." Festivus traditions invented for the show include the unadorned aluminum pole (Frank rejected tinsel as “distracting”), the meatloaf-shaped dinner meal, and the Feats of Strength. But my favorite Festivus activity is unquestionably the Airing of Grievances, which Frank announced with this rousing preamble: “I got a lotta problems with you people, and now you’re gonna hear about it!”

I celebrated Festivus for many years on my old blog (you can read all my “grievances” posts here). This year I’m reviving the custom not with a list of grievances but with a single word that both distills the grievance spirit and gives me a chance to complain. And that makes me happy!

The word is kvetch, and I gotta problem with how some of you are pronouncing it.

The noun and verb kvetch came into English from the Yiddish verb kvetshn, which in turn was adapted from German quetsche, which means “crusher” or “presser” and in which qu is pronounced like kv. Kvetch can mean “squeeze” or “eke out,”1 but most of the time it means, as Leo Rosten puts it in The Joys of Yiddish, “to fret, complain, gripe, grunt, sigh.” (Elsewhere I’ve seen the definition “to carp unduly,” which I like because “carp” reminds me of gefilte fish.)

Kvetch is a surprisingly recent arrival into English, and specifically American English: The OED’s earliest citation for the noun (an unpleasant person; a person who gripes a lot) is from 1936, and for the verb from 1950. Both citations are North American.

Here’s my kvetch: To give kvetch its proper tang, you need to pronounce it as a single syllable, with no vowel intruding between the K and the V. If you’re saying ka-vetch, the way I know some of you are, you’re doing it wrong.

If you’re an English-speaker who didn’t grow up surrounded by Yiddish-speakers, as I did, this single-syllable pronunciation may seem challenging, because we don’t have the /kv/ consonant cluster in English. But it shows up in other languages. In Yiddish, in addition to kvetch, there’s kvell, which means approximately the opposite of kvetch: to beam with immense pride and pleasure. Yiddish also has kvitch: to squeal. Russian has kvass, the fermented barley beverage. Norwegian has kvess, to sharpen.

What do these words have in common? They’re pronounced as single syllables.

Have you been inserting a vowel after the K in kvetch? Then try Yiddishizing your speech. The kv phoneme originates farther back in the upper palate than other K-onset words, almost like a hacking noise, and ends with a quick bite of the lips (a labiodental fricative).

I’ll depart from all this kvetching to note that the madeupical Festivus holiday has enjoyed a robust afterlife since “Seinfeld” went off the air in 1998. The Festivus Games is in its fifth year as “a functional-fitness competition for the rest of us.” (“No fire breathers!”) FestivusWeb will tell you how to decorate your aluminum pole (don’t). You can buy Festivus chocolate bars, a Festivus board game, and a wide assortment of other Festivus tchotchkes.2 So much for “playful consumer resistance. Sometime this week the Tampa Bay Times will be airing its readers’ grievances.

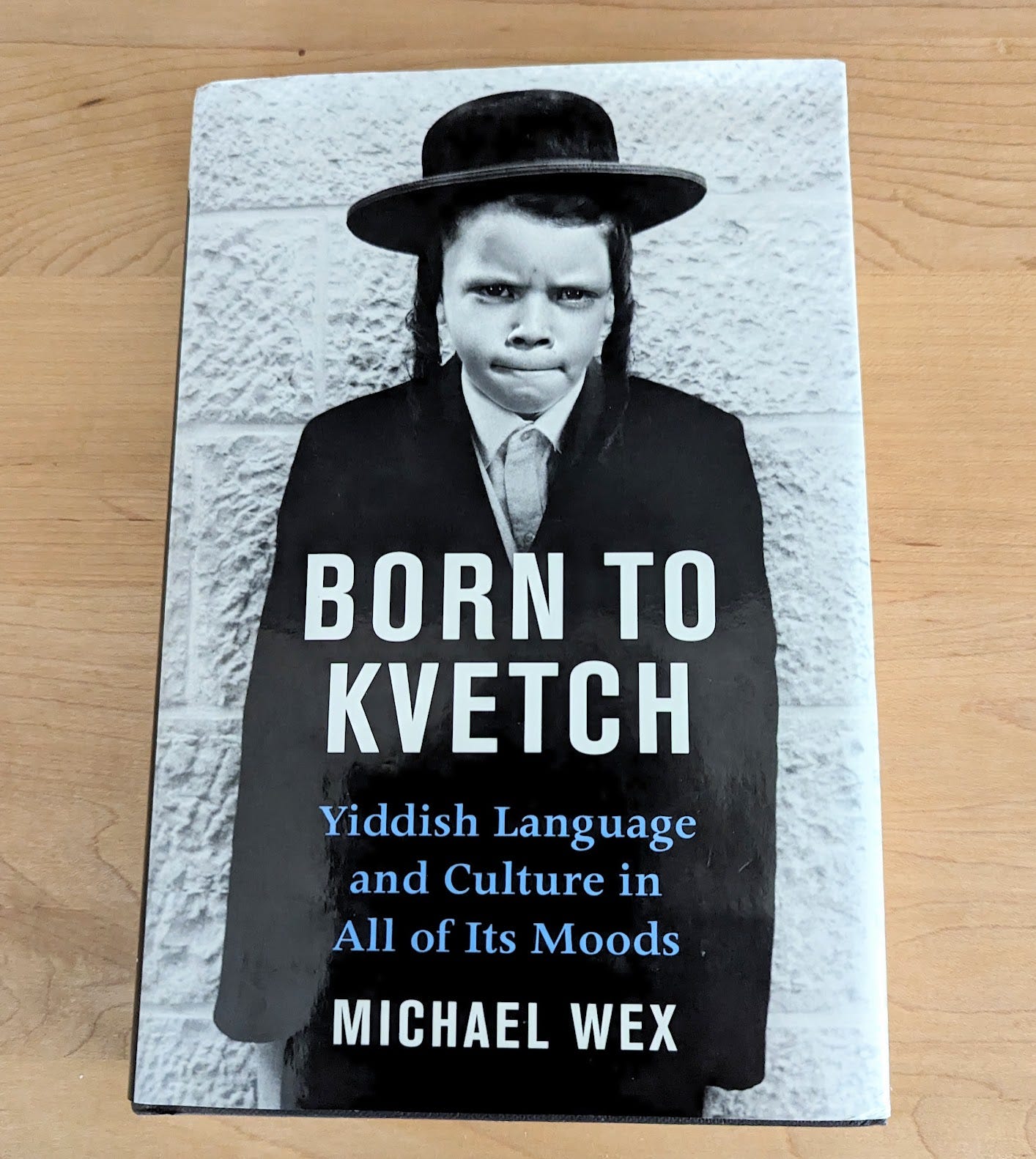

Finally, here is the consummate kvetching joke, which I’ve adapted from Michael Wex’s Born to Kvetch:

A man boards a train and sits opposite an older man reading a Yiddish newspaper. Half an hour goes by. The old man puts down his paper and starts whining loudly. “Oy, am I thirsty … Oy, am I thirsty … Oy, am I thirsty…”

The other man can’t stand it a minute longer. He gets up and walks to the water cooler at the far end of the car, where he fills two cups with water. He walks back to his seat and hands one cup to the old man, who gulps it down. The old man accepts the second cup and drains it as well. He sighs in gratitude.

Then the old man leans back, raises his eyes to the ceiling, and says just as loudly as before, “Oy, was I thirsty ...”

Happy Festivus to all!

Or, apparently, “to strain at stool.”

Another American-Yiddish word. The OED tells us its first appearance in English-language print was in Leo Rosten’s The Joys of Yiddish, originally published in 1968. That doesn’t mean it hadn’t been circulating long before then, though.

I would love to have heard Buddy Hackett perform the "Oy, am I thirsty" joke.

"Madeupical". It took me a while. Nice.