Word of the week: Doubt

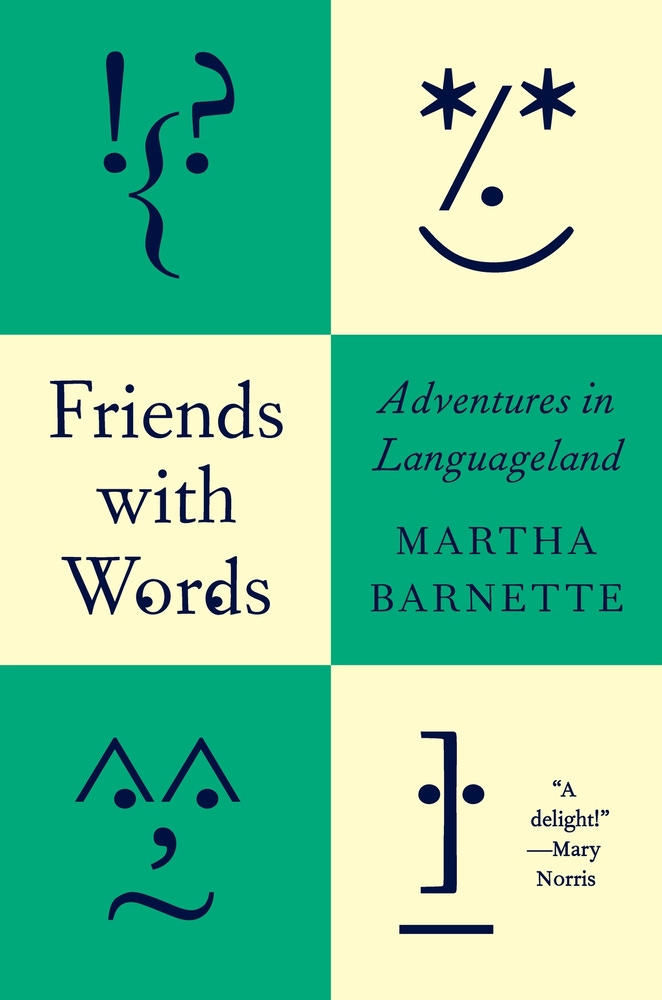

A late discovery and an excuse to preview Martha Barnette's new book about language.

If this post is neither as timely nor as topical as many of my WotW posts, that’s because I drafted it on Friday night, before Donald Trump bypassed Congress to authorize dropping “a full payload of BOMBS” on an Iranian nuclear facility and then bragged about the strike on Truth Social, the social media site he owns. (He signed off in his customary weird manner: “Thank you for your attention to this matter.”1)

has written about nuclear on his Lingwistics newsletter, if you’d prefer to stick to ripped-from-the-headlines etymology. On the other hand, maybe doubt is a word we should be taking a lot more seriously.It’s not that I was unfamiliar with doubt or that I had any doubts about its meaning. The surprise, this late in my life, was doubt’s origins, which I learned from Friends with Words: Adventures in Languageland, a forthcoming book by Martha Barnette, the co-host (with Grant Barrett) of the podcast and public radio show A Way with Words. Friends with Words will be published on August 5; the publisher, Abrams Books, kindly sent me an advance review copy.

Here’s what I hadn’t known: that doubt is related to duo (and double and duel), from a Latin root that means, duh, two. How and why are those words related? Because, Barnette writes, Latin dubare means “‘to hesitate to make a choice between opinions or courses of action,’ presumably between two of them.”

Which makes perfect sense! But it was a revelation to me.

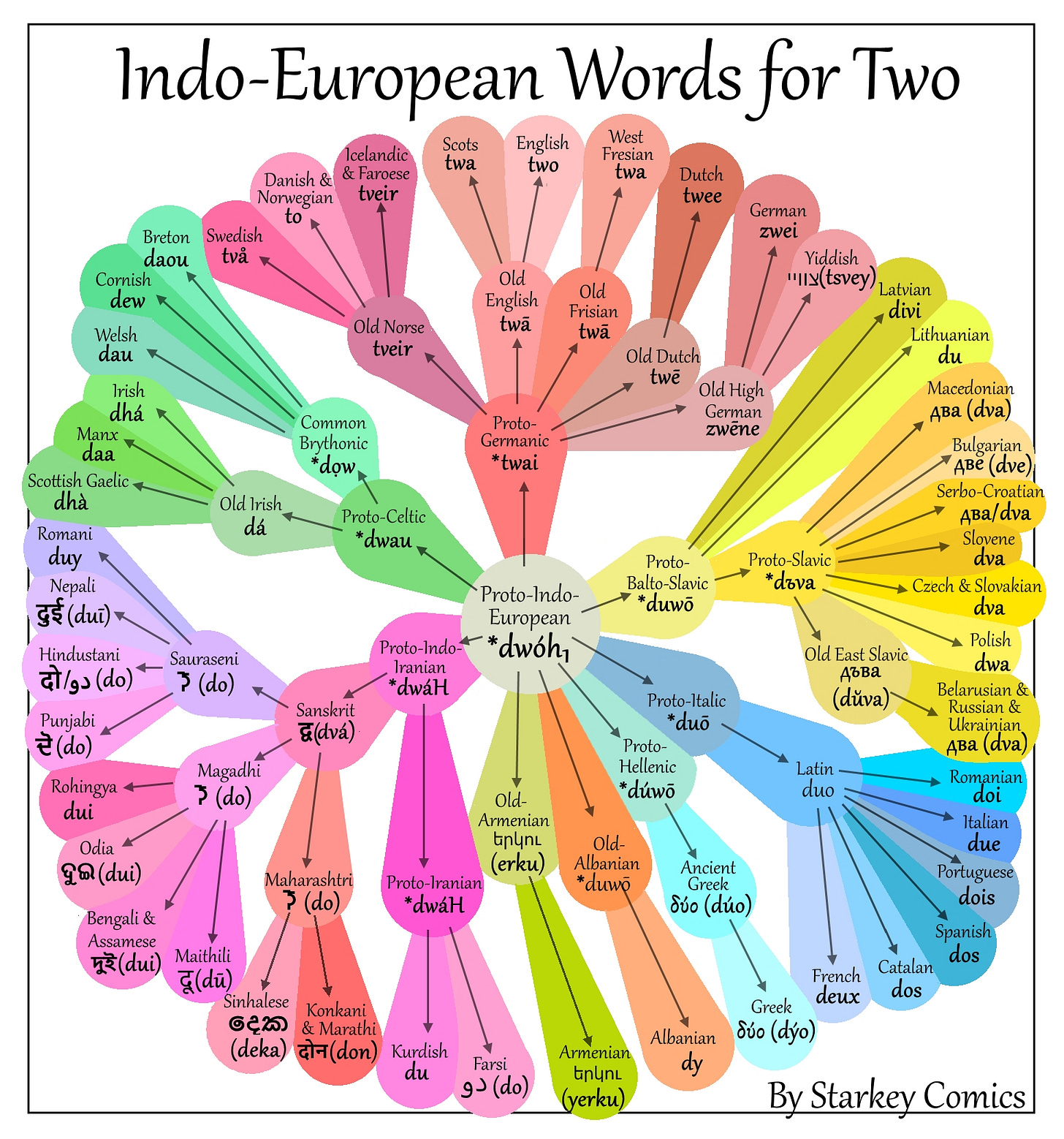

And here’s the kicker: Before English adopted doubt from French dote — to hesitate, to waver — around 1200, Old English had had the same general idea. Doubt replaced twēo, which, Barnette points out, is related to Modern English two. When you doubt, you are “of two minds” about something. The ultimate source for all these two words is conjectured to be the Proto-Indo-European root dwóh, which has also given us Spanish dos, French deux, Punjabi do, Polish, dwa, and so on.

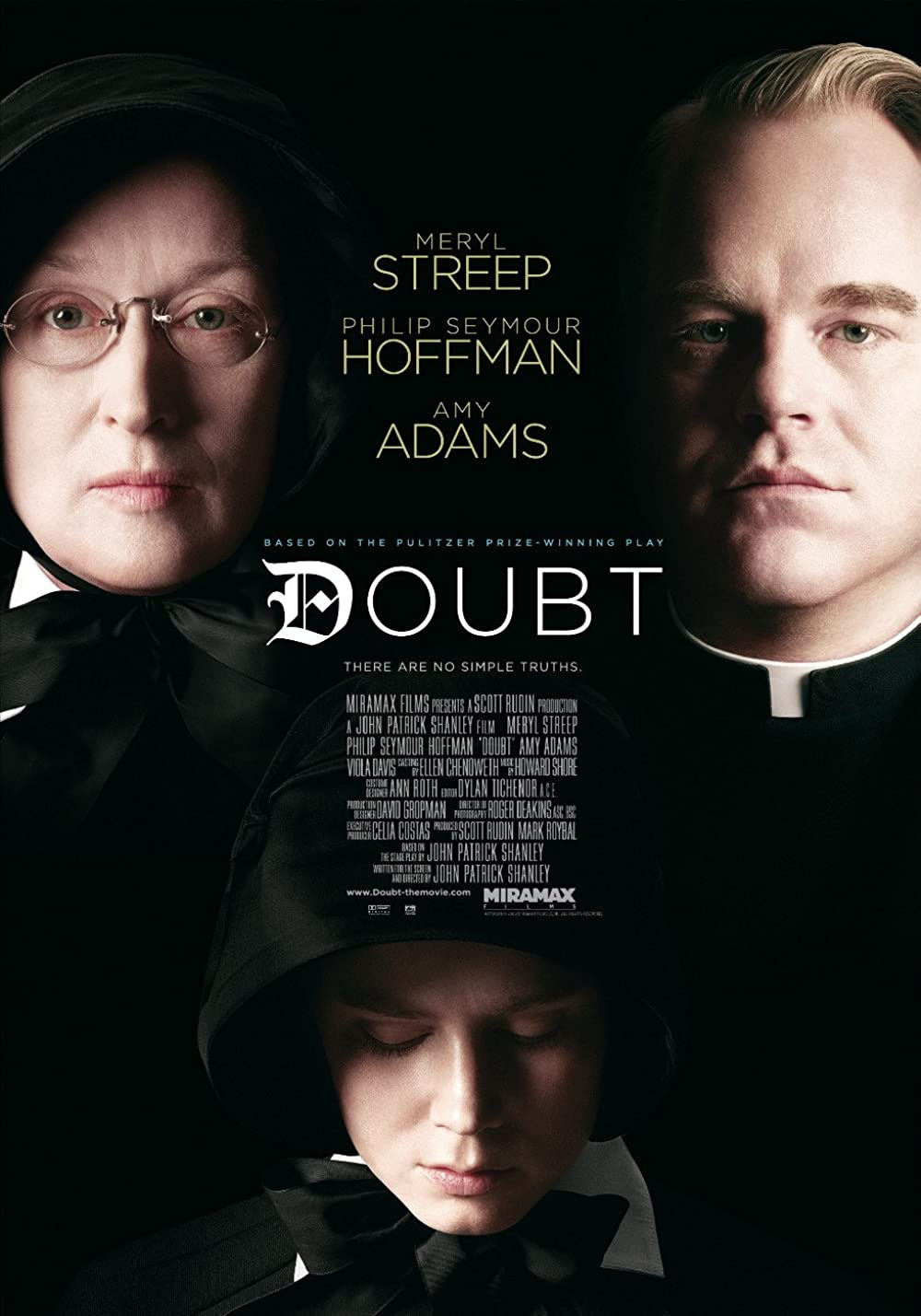

In English, doubt also carries additional shadings of “fear” and “distrust.” A redoubtable person (the word entered English in the late 1300s) is someone to be feared; in Christian theology, according to the OED, doubt has a specific sense of “uncertainty as to the truth of Christianity or some other religious belief or doctrine.” Those multiple meanings shimmer in the title of John Patrick Shanley’s 2004 play Doubt, which was adapted into a 2008 film.

I kept delving into doubt and making additional discoveries:

Beyond a reasonable doubt, the burden of proof for criminal conviction in the U.S. and in other adversarial justice systems, originated in Christian tradition, where it had a different meaning: “A person who experienced doubt yet convicted an innocent defendant was guilty of a mortal sin. Jurors fearful for their own souls were reassured that they were safe, as long as their doubts were not ‘reasonable.’ Today, the old rule of reasonable doubt survives, but it has been turned to different purposes. The result is confusion for jurors, and a serious moral challenge for our system of justice.” (From a summary of The Origins of Reasonable Doubt, by James Q. Whitman, published in 2016.)

To give [someone] the benefit of the doubt first appeared in print in 1848, according to the OED. It can be used casually today, but it originally meant “to give a verdict of Not Guilty where the evidence is conflicting; to assume his or her innocence rather than guilt; hence in wider use, to incline to the more favourable or kindly decision, estimate, or the like.”

Fear, uncertainty, and doubt first appeared in print in the 1920s in a Roman Catholic publication. By 1975 the phrase had been distilled into an acronym, FUD, and had gone secular as a sales and marketing tactic. Gene Amdahl, a computer scientist who left IBM to found Amdahl Corp. in 1970, is credited with this definition of FUD in 1975: “FUD is the fear, uncertainty and doubt that IBM sales people instill in the minds of potential customers who might be considering Amdahl products.” The idea, according to The New Hacker’s Dictionary (1991), “was to persuade them to go with safe IBM gear rather than with competitors’ equipment.”2

“The opposite of faith is not doubt, it’s certainty.” The quote has been attributed to the German-American philosopher Paul Tillich (1886–1965), but I’ve been unable to locate it in that form. (The closest I’ve found is this passage from Tillich’s 1975 book Systematic Theology: “But doubt is not the opposite of faith; it is an element of faith. Therefore, there is no faith without risk.”) A more likely source is a 2014 tweet in which American writer Anne Lamott came up with a paraphrase, or an extrapolation: “Paul Tillich said that the opposite of faith is not doubt — it’s certainty. Some of most profound spiritual words ever. Score one for mystery.”

I’ll be publishing a more extensive review of Friends with Words closer to its publication date. In the meantime, pre-order the book!

“It’s a weirdly stiff expression. It carries the bureaucratic heft of an HR email about which snacks are now forbidden in the break room, or that of a lawyer signing off an email about a pressing document that won’t e-sign itself. Given the source, though, it feels more like the boss reading all of America the riot act.” — Fast Company, April 23, 2025. Mark Harris calls it “the dictated-but-not-read presidency.”

Also expressed as “Nobody ever went broke buying IBM.”

A great entry, Nancy! (Doubt is my favorite performance of MS's!)

Thanks Nancy!