In the eighteenth century, when John Adams called Alexander Hamilton “the bastard brat of a Scotch pedlar,” both bastard and brat were poison-tipped slurs. In 2024, however, brat is enjoying a vigorous rehabilitation as a term of honor, or at least empowerment.

For proof, I offer three cultural artifacts, all released earlier this month.

Exhibit A is Brat, the new album from 31-year-old British singer Charli XCX, née Charlotte Emma Aitchison. (“Charli XCX” was her MSN Messenger screen name.) The title is an apparent self-reference — “I’m prepared for people to think I’m a bitch,” she told an interviewer — even if 31 seems a bit long in the tooth for brattiness.

The album has been something of a sensation. “I’ve been brat-pilled1,” confesses fashion Substacker

, who writes that “something about the brashly simple arial-narrow-font-on-puke-green album cover made me want to listen.” The color is “brat green,” she decides:how would you describe this green?

lime? slime? chartreuse? mold? it’s an in your face green, a puke green, a rotting green, an underbelly of the human condition green. and it’s blowing up online. a color trend has been born. on reddit, people are asking for advice on where to find brat green makeup and nail polish. depop sellers—entrepreneurial as ever—now offer DIY brat green bows for $18. social media profile pictures are turning brat green en masse.

Exhibit B is Brats, a documentary directed by actor and writer Andrew McCarthy (St. Elmo’s Fire, Pretty in Pink, Mulholland Falls) based on his memoir Brat: An ’80s Story (2021). (It’s streaming on Hulu; watch the trailer.) Forty years ago, McCarthy was a member of a group of young actors — Emilio Estevez, Ally Sheedy, Molly Ringwald, Rob Lowe, and others — fatefully dubbed the Brat Pack; in the film, McCarthy tracks some of them down in an earnest attempt to discover whether they were as scarred by the label as he was. (Short answer: Mostly not.)

And Exhibit C is Brat, the debut novel by 28-year-old British Gabriel Smith. “We meet our ill-tempered protagonist—the story’s titular ‘brat’—at a low moment, but not yet at rock bottom,” says the publisher, Penguin Random House. Like the album and the documentary, this Brat was released in the first week of June, henceforth to be celebrated as Brat Week.2

I haven’t read the novel, but I’ve listened to a bit of the Charli XCX album, watched the whole Brats film, and researched the history of brat. And then, as I was going over my notes, I stumbled on Emma Madden’s June 14 story for the New York Times about the sudden ubiquity of “brat” in popular culture, signaling “an intense identification with the term — and a shift in mind-set.”

The shift has been centuries in the making. The word’s origin is uncertain, but it may come from Old English brat, a coarse cloak. In later centuries a brat was a child’s pinafore or apron. In the sixteenth century, brat emerged as an often-contemptuous way of referring to a young child; “beggar’s brat” was a frequent collocation.

I remember thinking (or learning?) that brat was shortened from bastard. I was mistaken. Etymonline does point to a connection, though: “In earliest uses the implication is of an unwanted or unplanned child rather than a reference to behavior; differing from a bastard in that a married couple might have a brat.” A brat later became a child who was “ill-mannered” and “annoying,” and, eventually, “indulged” (as in “spoiled brat”). “Military brat” and “army brat” emerged relatively late, in the 1960s; the Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang informs us, to my surprise, that a “service brat” referred especially to girl-children.

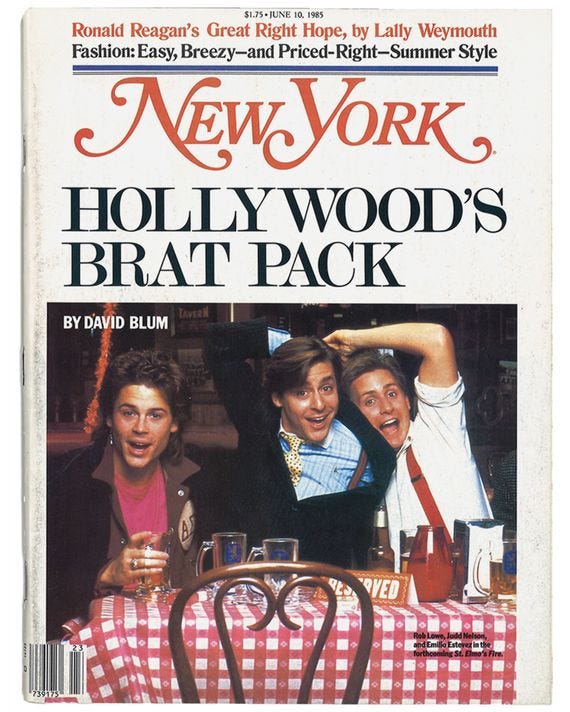

As for “brat pack” (frequently capitalized), it was the invention of David Blum, writer of a June 10, 1985, cover story for New York magazine. Blum hung out at Hollywood’s Hard Rock Cafe with “a group of boys” — they were in their early 20s — “who seemed to exude a magnetic force.” This, wrote Blum, was “the Hollywood ‘Brat Pack’”:

It is to the 1980s what the Rat Pack was to the 1960s—a roving band of famous young stars on the prowl for parties, women, and a good time. And just like Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Peter Lawford, and Sammy Davis Jr., these guys work together, too—they’ve carried their friendships over from life into the movies.

(The Sinatra gang was the second coming of the Hollywood Rat Pack. The OG RP, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, included Humphrey Bogart, Errol Flynn, and Nat “King” Cole. According to one story, Lauren Bacall, who was married to Bogart, gave the group its name when she saw them return from a trip to Las Vegas and sniped, “You look like a goddam rat pack.”)

In the Brats documentary, Andrew McCarthy beards Blum in his den, or his library, to talk about how a clever, casually coined label altered the course of many careers. Blum is unrepentant; in a reminiscence published last week in Vulture (“I Called Them Brats, and I Stand by It”), he defends his choice:

In truth, the Brat Pack has been ingrained as a happy memory for a generation of moviegoers who came of age in the 1980s, learning life lessons from the likes of directors John Hughes, Francis Ford Coppola, Cameron Crowe, Paul Brickman, Joel Schumacher and Amy Heckerling. They’re avatars of a once-vibrant celebrity culture that minted movie stars to last a lifetime, not a year or two. The epic, enduring star power of Brat Packers like Cruise, Lowe, and Penn — with Robert Downey Jr. and Matthew Broderick right there with them — have [sic] kept the Brat Pack brand alive and well. They’ve racked up a remarkable record of durability in an industry that now casts actors aside on a daily basis.

Interestingly, neither Blum nor McCarthy notes the existence of a parallel Brat Pack: the literary one that encompassed writers like Bret Easton Ellis (interviewed by McCarthy for the film, but not about books), Jay McInerney, and Tama Janowitz — all in their early to mid-60s now, like their Hollywood counterparts. This strikes me as a missed opportunity to say something about Generation X — Generation Brat? — a cohort that otherwise clamors ceaselessly for recognition.

No discussion of brat and popular culture would be complete without a nod to Bratz, the dolls with oversize heads, almond-shaped eyes, and skinny bodies clad in skimpy clothing. “They look like pole dancers on their way to work at a gentlemen’s club,” wrote Margaret Talbot in a 2006 New Yorker article, “Little Hotties.” Bratz —“the girls with a passion for fashion,” as their tagline put it — were introduced in 2001 by MGA Entertainment, which pitched them as “bratty teens” and sold them as a set of four. The franchise also had a passion for the letter Z, as evidenced in the names of spin-off properties: Bratz Kidz, Bratz Boyz, Bratz Babyz, Bratz Lil’ Angelz, and Bratzillaz. (Bratz Babyz arrived “with makeup, lacy lingerie, and bikinis, and bottles slung on chains around their necks,” Talbot reported. Bratzillas were witches with special powers; the line was later rebranded as House of Witchez.) The dolls, with their trendy names (Yasmin, Cloe, Sasha, Jade), ethnically ambiguous features, and provocative wardrobes were a huge hit with young girls and a source of hand-wringing and soul-searching for their parents. Bratz were “the outcasts of the dolls,” the brand’s social-media content creator, Mar Cantos, told W magazine in 2021.

No one would call them outcasts now. The thriving Bratz brand has spawned a slew of animated feature films, one live-action film (Bratz, 2007), and several TV and web series, including “Alwayz Bratz.” In 2023, Bratz launched a line of sultry-looking dolls in collaboration with media personality Kylie Jenner, who’s been labeled a “spoiled brat” a few times herself.

UPDATE: I’d somehow missed Ben Zimmer’s take on brat for his Wall Street Journal “Word on the Street” column. He covers much of the territory I explore here, with a bonus quote from Andrew McCarthy. Related: Check out Ben’s crossword puzzle on Slate.

For more on the many ways “-pilled” has infiltrated our vocabulary, see my November 2023 post, “So Many Ways to Be -Pilled.”

With a helping or three of grilled brats, short for bratwursts. German brat is “meat without waste”; wurst is “sausage.”

As has been noted, the only brats I favor are those that come with sauerkraut.

Surely there's a connection to be drawn between rat packs turned brat packs and the other big trend of the summer, rat-like heartthrobs. But I'm not sure what it is.