Back in the dial-up-modem era I was briefly a member of The WELL1, which was founded in 1985 by Stewart Brand and Larry Brilliant and is still alive and, well, well, making it one of the oldest active virtual communities. Before I left — I just couldn’t handle the heavily Grateful Dead–centric vibe — I soaked up a lot of WELL-ish acronyms that were novel back then and have since become part of generally accepted vocabulary: LMAO, LMFAO, ROFL, TTYL, BRB, RTFM, and so on. One of my favorite WELL-isms, though, never really found its way out of the walled (or WELLed) garden. That term was S!MT!!OE!!! — it was important to get the exclamation points exactly right — and it stood for Sets! My Teeth!! On Edge!!!

I loved how S!MT!!OE!!! covered things that we might now call “cringe”: too annoying to overlook but not worthy of a full-scale flame war (another term I learned via The Well). The things that set my own teeth on edge tended to be language-usage things. Things that made me gnash my molars and count to 100 before I said something I’d regret.

Well, my friends, the time for gnashing and counting has passed and the time for regrettable utterances has come. Here’s a little list of errors I’ve seen lately (or repeatedly), often right here on Substack, that S!MT!!OE!!! — errors a good editor would catch, but a hurried self-editor sometimes doesn’t, or doesn’t even recognize as errors. I’m not referring to the usual suspects: its and it’s, their, there, and they’re, who’s and whose2, your and you’re, lie/lay/laid/lain. I’m talking here about graduate-level boo-boos. Many of you — maybe most of you — already avoid these errors. Feel free to share this post with someone who doesn’t.

What entitles me to be so bossy? I’ve been a proofreader, a copyeditor, and an assigning editor for newspapers, magazines, and books. I’ve also done time as a newspaper reporter, magazine writer, marketing copywriter, and book and blog author. I read style guides — the ones about language usage — for fun. I fret (more than you can possibly imagine) over my own typos and mistakes. I care about clarity. And I read. A lot. And so I see a lot of stuff that S!MT!!OE!!!

For example:

It’s in regard to and with regard to, singular. Give your “regards” to Broadway.

Never start a sentence with “albeit.”

Just forget about “albeit.”

Resist the temptation to insert “of” in phrases like “not too big a deal.” (It’s called intrusive of, if you want to get technical.) And speaking of of, here’s what

says in Dreyer’s English about based off of: “No. Just no.” (Use based on.) Strunk and White weren’t right about everything, but they were right about “omit needless words.”Intact is one word. Keep it intact.

In case, on the other hand, is two words.

Likewise more so.

Aha, however, is one word. Please don’t write “a-ha” or “ah-hah” or anything except “aha.” OK, fine, add an exclamation mark.

Everyday, closed up, is an adjective meaning mundane or quotidian: “an everyday occurrence.” Use every day, two words, when you’re talking about each and every 24-hour period.

Versus is a two-syllable word. The abbreviation is vs., also pronounced versus, with two syllables. “Verse” is a form of poetry.

The adjective advanced means “modern” or “at a higher, more difficult level”: the next rung on the ladder after beginning and intermediate. The adjective advance means “prior.” That soon-to-be-published manuscript is an advance copy, not “advanced.” Your email about an upcoming event is advance notice, not “advanced.”

Phenomena and criteria are plural. The singular forms are phenomenon and criterion. Because Greek.

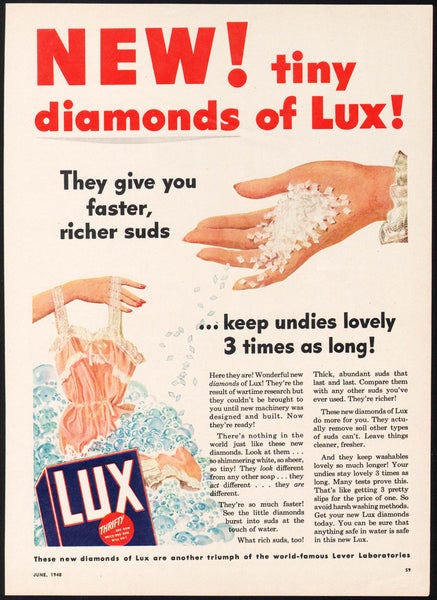

Luxe is a French-into-English noun meaning “luxury”; in copywriting, it’s sometimes used as an adjective. Lux is a brand of detergent. (Luxe, by the way, is also a brand name; the Luxe company makes bidets. I myself own a Luxe bidet attachment — this one— and I recommend it highly.)

A dessert island — accent on the second syllable of dessert — would be a floating parcel of land whose primary resources were peach pies and chocolate layer cakes. A desert island — accent on the first syllable of desert — is deserted.

It’s free rein and a tight rein. Think of horses rather than princes, who reign.

The past tense of cast is cast. The past tense of broadcast is broadcast. The past tense of forecast is forecast. There is no “casted.”

The past tense of text is texted.

Here’s something I recently saw at San Francisco’s de Young Museum, which ought to know better: “For the photographs in his series, Worlds in a Small Room, made for Vogue magazine . . .” That comma after “series”? It leads us to believe that this is the photographer’s3 only series, which it definitely is not. Worlds in a Small Room is essential information here: If you remove those words — that clause — the sentence loses its meaning. It’s the difference between “my daughter, Tiffany” — he has only the one daughter — and “my daughter Tiffany” — one of several daughters (or just two, if we’re thinking of the same Tiffany). This error often appears with personal titles: It’s “Meet Editor-in-Chief Anna Wintour,” not “Meet Editor-in-Chief, Anna Wintour,” and “Our guest is name developer and Substacker Nancy Friedman” — no comma. If you want to explore further, I refer you to restrictive and nonrestrictive clauses.

You flush out a clogged drain. When you’re adding substance to a topic, you’re fleshing it out: putting flesh on its bones, so to speak.

Are you writing on a typewriter? No? Then stop double-spacing after periods. Don’t argue with me.

Testimony is a written or spoken statement from a witness; testament is visible or tangible proof of something. “The victory is a testament to her determination”— not a testimony. There are also the biblical Testaments, Old and New, but we don’t need to go there.

“$50 million dollars.” Really? What does $ mean? What does “dollars” mean? Why are you repeating yourself?

“There were only about a 100 of them in use.” This phrase somehow made it past the Los Angeles Times copy desk. (Does the Times still have a copy desk? Maybe not.) The problem is this: The numeral “100” is pronounced “one hundred” (not “hundred”) and does not require the article “a” in front of it. Go ahead and use “a” if you’re writing “a hundred monkeys” or “a 100-year-old woman.” (And while you’re at it, use the right number of hyphens in “100-year-old.” That number is zero when you’re writing about something that’s 100 years old.)

Remember when you set the clocks forward an hour (or your devices did it on their own)? That means we’re living in Daylight Saving (not Savings) Time, so your abbreviation should be EDT or PDT or MDT or [fill in the time zone], not EST, etc. The S in EST means “standard,” and we’re off the standard now, even though Daylight Time does seem to last forever. Better still, just drop the middle letter. Everyone will know what 5 p.m. ET means.

Simplistic is the bad kind of “simple.”

Likewise, you probably mean minimal or maybe minimalist, not “minimalistic.”

This one is very specific, but if you write about fashion and want to be viewed as an authority, you should know which way the accent goes in “Hermès.” It’s pronounced air-MEHS, not air-MAY, by the way.

It isn’t a “palette cleanser” unless you’re up in your garret removing the paint from the slab (the palette) on which you mix your pigments. You probably mean palate cleanser: “a serving of food or drink that removes food residue from the tongue allowing one to more accurately assess a new flavor.” Palate cleanser can be used metaphorically, too. A pallet is a flat transport structure or a straw bed.

Macho is an adjective. The noun is machismo.

Wallah is Hindi for “a person in charge.” You probably mean voilà, which is French for “See there!” Note again the direction of the accent.

Sight, site, cite: Frequently, lamentably confused. You go sightseeing at tourist sites and then cite your sources when you write about the experience.

Lead is present tense; it rhymes with secede. The past tense of lead is spelled led and rhymes with bread. Yes, this is baffling to anyone who knows that read is present tense and read is also past tense, but pronounced differently. Likewise, lose and loose should not be confused: Lose rhymes with choose and bemuse; loose rhymes with obtuse and deuce. How does anyone ever learn English? It’s a mystery.

NOTE: Errors in this post are entirely attributable to McKean’s Law: “Any correction of the speech or writing of others will contain at least one grammatical, spelling, or typographical error.”

Want more language-y bossiness? Get yourself a copy of Dreyer’s English, subscribe to

’s fine Substack, check out June Casagrande’s Grammar Underground blog and podcast, read on “The Word You Want Is Spelled Y-E-A-H,” and listen to Grammar Girl, who isn’t bossy at all and in fact is a lot nicer than I can ever hope to be.WELL is an acronym, or backronym, for Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link.

Yes, you can — and should — use whose with inanimate or abstract objects: “An event whose time has come.” Definitely, absolutely not “An event that’s time has come,” although I’ve seen the latter too many teeth-on-edge times.

Irving Penn. It’s an excellent exhibit, up through July 21.

I'm nonplussed that you didn't include "nonplussed." Or "unphased."

Come for the copyediting tips, stay for the bidet recommendations - that's quality content!