Recommendation: "Confessions of a Good Samaritan"

Could you donate a kidney to a stranger? Would you? Should you?

“The fundamental weakness of Western civilization is empathy,” the richest man in the world told a global podcast audience last month. He went on to qualify his declaration, slightly, by stipulating that weaponized empathy was “the issue.” And although he didn’t go into more detail, I’m guessing that by “weaponized” he meant “turning people’s better impulses against them.”

I’ve been thinking about this remark and this worldview — and about how we get from “empathy is weak” to “Social Security is a Ponzi scheme” — because I recently watched, for the second and third times, a documentary about empathy, altruism, and human kidneys. The filmmaker and her subjects would probably agree that empathy is “the issue” only because there isn’t enough of it.

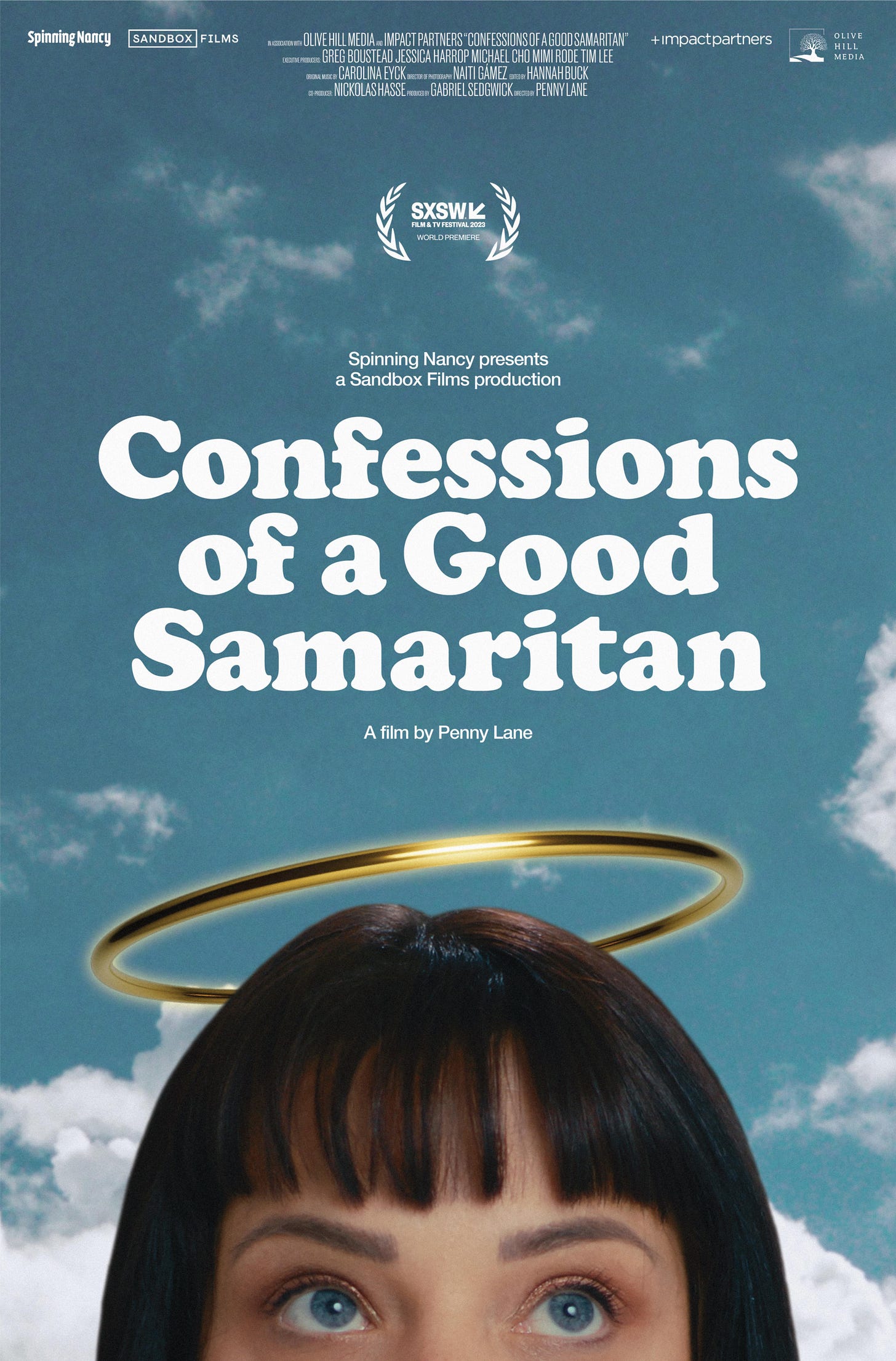

I first saw Confessions of a Good Samaritan in April 2023, at the San Francisco International Film Festival; there was a Q&A afterward with the appealing and relatable director/protagonist, Penny Lane. I loved the movie and couldn’t wait to tell everyone I knew about it, but if it had a theatrical release in the Bay Area it must have been fleeting, and I missed it. It’s finally streaming on Netflix; I encourage you to watch it.

Good Samaritan’s subject is not the New Testament story (although it does come up) but rather “altruistic” or “nondirected” organ donation, in which the donor and the recipient don’t know each other. In 2019 Lane, a healthy 41-year-old New Yorker, donated one of her own kidneys — you only need one — to someone she didn’t know, becoming one of the 2 percent of living kidney donors who donate to strangers. The film is about her operation and much more: the history and ethics of organ transplantation, the kidney-transplant shortage, the physiology of altruism. (It turns out altruists have larger amygdalas than their opposite numbers. Psychopaths, in case you had any doubt, score extremely low on empathy.)

From my first viewing I loved Good Samaritan for its honesty, its curiosity, its quirky humor, and its dreamy soundtrack. Two years later, as we have plunged ever deeper into this era of enshittification, it speaks to me even more urgently. I’m apparently not alone: The film got rave reviews from critics and has a 100 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

One reason I’m a little obsessed with Confessions of a Good Samaritan it that last year an acquaintance of mine died while waiting for a kidney transplant. His was hardly an isolated case: There are thousands of Americans enduring dialysis, or dying, because there aren’t enough donor kidneys to go around. If I had died first, say in a car crash, one my my kidneys might have gone to my friend, because I’ve checked “organ donor” on my driver’s license. But I didn’t, and it didn’t, and he died.

In many respects, though, I’m an ideal candidate for living organ donation. I’m healthy, I don’t have a spouse or children to explain myself to, and I don’t have qualms about surgery. (On the two occasions when I’ve undergone minor procedures I asked for a camera to be angled so I could watch.) I donate blood four or five times a year; my donor card says I’ve done so 150 times so far. Granted, an invasive operation is a few steps beyond phlebotomy, but still: Why not?

Something else about me: I am by most standards a disgrace to the Jewish faith in which I was raised1, but two things I learned in all those religious-school classes have stuck with me, and I try to adhere to them. The first is Hillel the Elder’s famous quote, of which only the last part tends to be re-quoted: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? But if I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when?”

The second lesson is perhaps less famous among non-Jews, but it’s hugely meaningful to many of us, including me.

The Hebrew word that’s usually translated as “charity” is tzedakah, which actually means “justice.” (“Charity,” a Christian concept, comes from Latin caritas, which means “affection” or “caring.” Judaism sees things a little differently.) The medieval sage Maimonides enumerated eight levels of tzedakah: In the lowest form, you give grudgingly, in the next level you give willingly but meagerly, and so on. The very highest form of tzedakah is helping someone, or some group, to become independent of tzedakah. But the level just below that one is “giving assistance in such a way that the giver and recipient are unknown to each other.” Anonymously, that is, and with no recognition at all.2 That’s how I always choose to donate money. And it’s the guiding principle of altruistic, “Good Samaritan” organ donation.

Altruistic organ donations have been taking place for only about 25 years. At first, and for many years afterward, people who chose to donate to strangers were seen as weird, even a little unhinged. Who would do such a thing?

Well, I would. I haven’t yet, but I would3.

In fact, if I were to donate a kidney4 I would insist on it going to a stranger.5 I wouldn’t want or need to meet the recipient, although it would be nice to know they were doing OK.6

Toward the end of Confessions of a Good Samaritan, Penny Lane looks directly into the camera and wonders aloud about whether altruistic organ donation represents “moral progress.” She concludes that it does:

How else could you measure moral progress? If it’s not the gradual expansion of your sphere of concern from yourself to your immediate family to your neighborhood, to your community, to your nation, to the world, to all living things, what is it?

And if not now, when?

I’m still working on that. In the meantime, here are a few other things I’ve been thinking about:

It’s hard to say exactly when altruism began to be a dirty word in certain quarters, but one turning point came in 1990, when Chanel introduced a fragrance “for the man whose power of seduction lies in his strong, independent and elusive character.” That was one way of putting it. The fragrance was called Égoïste, which means, yes, “self-centered,” “self-seeking,” and “concerned with himself at the expense of others.” I vividly remember the appalling name and the 30-second ad that launched the brand, in which 35 glamorous women operatically yelled “Égoïste!” at some invisible asshole. (“Où es-tu? Montre-toi misérable! Prends garde à mon courroux! Je serai implacable! Ô rage! Ô désespoir! Ô mon amour trahi! N’ai-je donc tant vécu que pour cette infamie? Montre toi, Égoïste!”) The name and the campaign celebrated terrible behavior, and look where we are now. You can still buy the fragrance, by the way, in case you really want to tell the world just what kind of reeking narcissist you are. (I wish I could tell you that Chanel also launched a counter-brand called Altruiste. Fat chance.)

If 1 in 10,000 Americans donated a kidney — a tiny number — we could completely eliminate the kidney-transplant waiting list.

Finally, as a palate cleanser, here’s a gift link to a lovely New York Times story, reported by the peerless Dan Barry, about a family that chose the other kind of organ donation, the “directed” kind: “Along the walls, family members, friends and hospital workers stand at attention, in somber respect for someone who, in his imminent death, is about to give life. It is a ritual called the honor walk.”

It was Judaism Lite, but Judaism nonetheless.

Related: My February 2021 story for Medium, “Stop Naming Buildings After People.”

FYI, there is no upper age limit for kidney donors, at least in the U.S., so you can rule that excuse right out.

Or a piece of my liver, which I have just learned is an option. Livers regenerate, you know.

Or, OK, one of my brothers. But that’s it.

It would be especially nice if I could be assured that the recipient absolutely was not a 53-year-old South African immigrant to the U.S. who happens to be the richest man in the world. Yes, I still have work to do, altruism-wise.

Thanks for footnote 6. Gave me a chuckle, because I so agree.

That line from the NYT story also stuck with me when I read it, Nancy.