I recently received a gift of a first-edition copy of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style (thanks, Beth O.!), and while I was searching for space for it in the “style guides” section of one of my overstuffed bookcases I discovered a book I hadn’t consulted, or even noticed, in years. Long ago I’d used the sales receipt as a bookmark, so I know when and where I’d bought it: April 12, 1994, at Levi’s Plaza Books (R.I.P.), 1255 Battery Street, San Francisco.

Yes, kids, I was sending and receiving “e-mail” in 1994. (The term had been in circulation since 1982.) In fact, by then I’d been using it for about five years, ever since a client set me up with an all-numerals Compuserve account.1 I’d been using Strunk and White even longer — since journalism school, when it was required reading. I must have spotted David Angell and Brent Heslop’s hot-off-the-presses Elements of E-mail Style at the bookstore and figured that A&H was a timely update to S&W.

How does it look in 2025? Let’s see!

Here’s the breathless opening to Chapter 1, “Write Right for the E-mail Medium”:

Faster than a speeding letter, cheaper than a phone call, electronic mail is the communication of the ’90s. The Electronic Mail Association estimates 30 to 50 million people use e-mail, and the number of users is growing at more than 25 percent per year.2

The number may have seemed impressive in 1994, but by 2024, according to Email Tool Tester, there were 4.48 billion email users worldwide. Email was definitely no passing fad. (On the other hand, if the Electronic Mail Association still exists, I’ve found no evidence of it. PC Magazine tells me that there was an Electronic Messaging Association, founded in 1983, that was folded into The Open Group, a technology-standards organization, in 2001.)

Angell and Heslop present six advantages to communicating by e-mail, all of them tied to the workplace: It eliminates phone tag; breaks down distance and time barriers; reduces telephone interruptions; “improves productivity” (ha!); flattens corporate hierarchies (as if!); and “enables people to circumvent many of the inefficiencies of the office place” (yeah, no).

Remember, this is early 1994. Netscape, the company that distributed the first widely available web browser, would be founded in April of that year, and by the end of 1994 there would be only a relatively paltry 1 million browser copies in use.3 (Here’s my source, a good history of the world wide web.) So e-mail, or email — the Associated Press Stylebook dropped the hyphen in 2011 — was what “computer connectivity” meant to most people. Email was the killer app.

Most of The Elements of E-mail Style’s 149 pages deliver general writing advice that would have been equally appropriate in the quill-and-parchment era: Use clichés sparingly; avoid redundancy; watch your irregular verbs (lie/lay/lain, forbid/forbade/forbidden); know the four sentence types (declarative, interrogative, exclamatory, imperative). The authors inject some levity with their example sentences: To illustrate “Write positively,” they offer “When you finish the report, Mr. Sisyphus, I have another one for you.” Much more agreeable than “If you finish the report”!

For the reader in 2025, though, the most entertaining sections of the book are the ones devoted to the 1990s experiments: stuff that seems primitive and quirky today but was startling and innovative then.

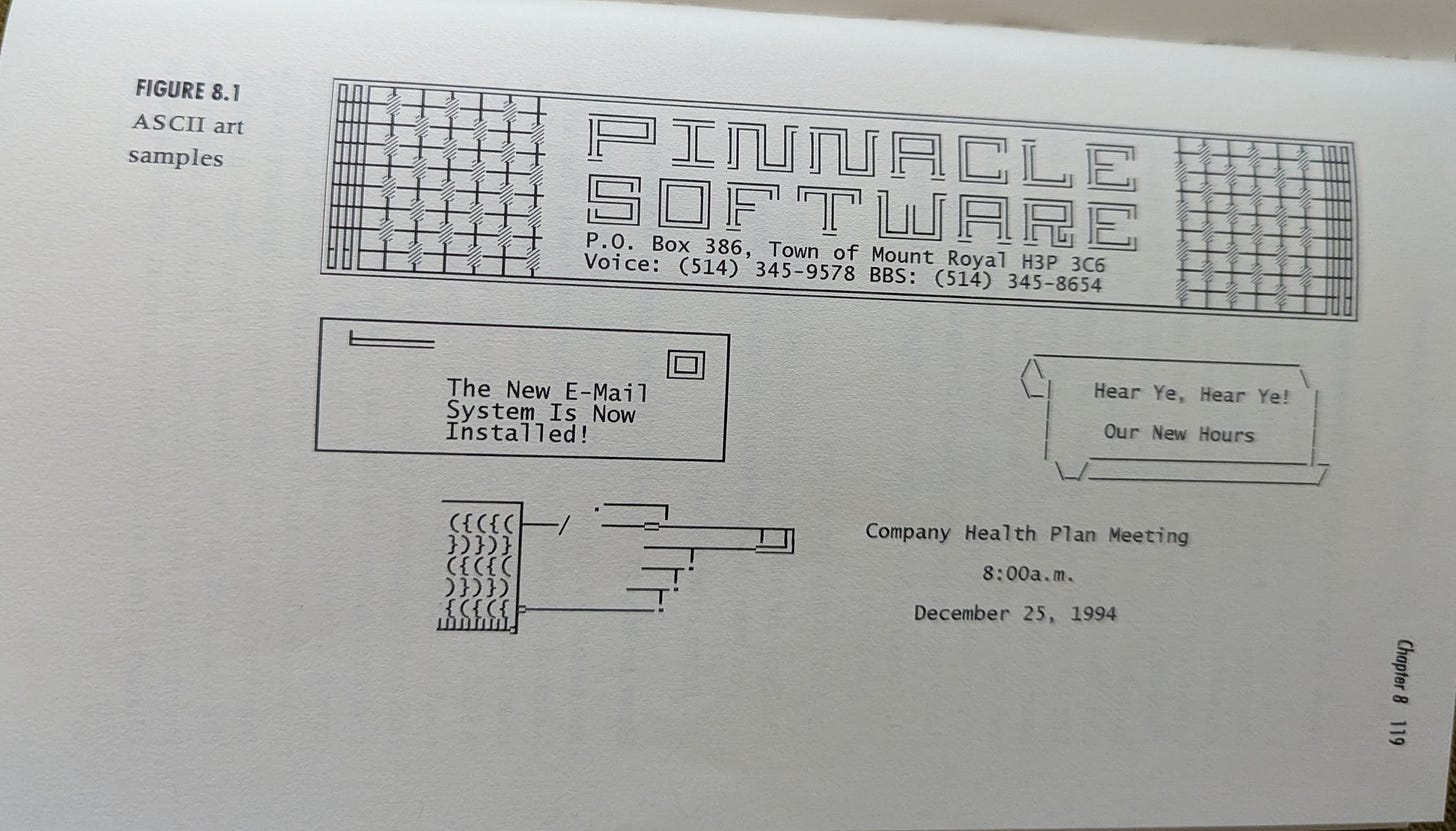

Inserting a photo or drawing into an email was a remote dream in 1994, so we (well, some of us) made do with ASCII art: images created from the seven-bit ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) character set. “Creative people have taken the simple ASCII characters and created sophisticated [sic] graphic art,” Angell and Heslop tell us. One of their examples:

So sophisticated! So, so time consuming.

Then there were “smileys,” aka emoticons, which is what we used before emojis came along to save us countless keystrokes.

I don’t remember ever using the “angry” or “happy confused” emoticons, but I love knowing about them. Also, if there’s an emoji for “happy sarcasm or smirk,” I doubt that it’s as clear and charming as :-]

In case you were wondering, emoticons had an inventor, Scott Fuhrman, who suggested them in 1982. They would eventually be supplanted by emoji (a portmanteau of the Japanese words for “picture” and “character”), which were developed in Japan the mid-1990s (some people say earlier) and which would be introduced by Google and Apple in the U.S. in 2008.

The Elements of E-mail Style was forward-thinking in its caveats about “sexist language,” which appear early, on pages 8 and 9: “Sexist masculine pronouns and gender-specific titles are rooted in our language like weeds,” the authors warn, before proposing better options. They also advise their readers to “be culturally aware for international e-mail”: It’s just good business, not to mention courteous, to provide metric measurements and generic terms instead of U.S.-centric brand names.

A glossary in the back of the book covers basic grammatical terms (what’s an adjective? what is sentence parallelism?) as well as then-current e-mail lingo. The entry for bozo filter says “See kill file”; I’d never heard of either. (The definition: “News reader filter program that allows you to screen out postings by a particular user or a particular subject.” I think today we’d just call it a block.) Also new to me: Net saints (“experienced Internet users who are willing to share their knowledge with newcomers”) and net weenies (“Internet users who enjoy insulting other users by posting flames of any kind, from spelling and grammar criticisms to just plain nasty messages”). Due for a revival?

One conspicuous absence from the glossary: spam. That’s because it first appeared in print with the sense of “unsolicited email” in May 1994, three months after Elements was published. It was novel enough then to require quotation marks, even in the trade publication Network World: “Internet users suffered another ‘spam attack’ last week, this time from a Florida public-access host user who flooded Usenet conferences with ads for a thigh-reducing cream.” By the following year, no quotation marks were needed. Spam had become just an annoying fact of computer life.

You can still buy The Elements of E-mail Style from various online merchants, including the big one that launched in July 1994, five months after the book’s publication. Although as one disappointed shopper complained in 2012, “This is an old book.” True then, truer now.

What current writing advice do you predict will be passé or incomprehensible in 2056?

Thanks to for suggesting over coffee that I publish a book review now and then! The Elements of E-mail Style may not have been the sort of literature she had in mind, but I appreciated the prompt nevertheless.

If you enjoyed this shallow dive into e-antiquity, you may also like my story about The WELL and the cyber-cad:

Word of the week: Cad

The only feature in the Sunday New York Times Style section that I read without fail is the advice column called “Social Q’s,” in which the very patient Philip Galanes answers questions about relationships, money, and the intersection of the two. The topics are usually present-day-ish (one of my favorites: “Who Gets the Cloned Dog in the Breakup?”), so …

At the time, that client was the only other person I knew who used email. To send a message, I would first call the client on my landline and ask him to turn on his modem. Only after he assured me that it was up and running would I hit Send.

I’d have written that statistic as “30 million to 50 million,” but I’m picky that way.

The Elements of E-mail Style covers “conventions for posting on the Internet” in an appendix that begins “The Internet is a patchwork quilt of more than 13,000 networks connecting over 15 million people.” A series of bullet points addresses “basic posting netiquette”: Be considerate of network resources; don’t spew (“Spewing is posting a large number of articles on the same subject and cross-posting to a number of newsgroups”); avoid flame wars (“Flames that have gone on for years are referred to as holy wars”), and “Don’t post an article that points out spelling and grammar mistakes you have discovered in a posted article.” Whoops, too late.

Oddly, all but one of those ASCII art samples include non-ASCII characters — I see box-drawing characters (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Box-drawing_characters) — which means that in the era of this book, they wouldn't have been a good choice for email: there'd have been a high risk of recipients seeing gibberish. (Though I guess back then we were more used to all kinds of email formatting problems, so maybe that risk was considered acceptable?)

Man, I could have used a bozo filter today!