I’ve tried multiple times to learn to code. Each time I’ve given up because the instruction was too basic, too fussy, too slow, or too pointless (or so I thought). I’ve taught myself just enough HTML to peek behind the curtain and fix some errors; anything more complicated seemed beyond my ken.

So when I first learned about vibe coding, several months ago, I was interested. It didn’t sound like coding it all. No zeroes or ones or pointy brackets! It sounded like something even a literature major like me could learn. It sounded like the fulfilment of programmer/author Ellen Ullman’s 2016 dream: “I dare to imagine the general public learning to write code.”

Here’s how Google defines vibe coding:

Vibe coding is an emerging software development practice that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to generate functional code from natural language prompts, accelerating development, and making app building more accessible, especially for those with limited programming experience.

In other words, if you can “talk” to an AI using regular words and sentences, you too can be a coder.

Naturally, there are billboards.1

Vibe coding is definitely “emerging.” The term was coined just seven months ago, in February 2025, by Andrej Karpathy, a 38-year-old Slovak-Canadian computer scientist whose achievements include “director of AI at Tesla” and “founding team at OpenAI.” He announced his big breakthrough in a tweet:

The emergence was enthusiastically embraced. Within weeks, vibe coding got an endorsement from New York Times tech reporter Kevin Roose,2.who wrote on February 27 that thanks to vibe coding he — a computing novice — had been “coding up a storm.” It was so easy! “You don’t have to know how to code to vibecode — just having an idea, and a little patience, is usually enough.” Usually. (Gift link.)

“Vibe coding isn’t just a gimmick — it’s already boosting productivity and creativity,” a developer site called Dev.to chirped in April. (Not just a gimmick. OK then.)

Vibe coding “is creating a new AI economy,” another boosterish article proclaimed, this time in Forbes. “AI is redefining entrepreneurship, allowing people with a vision and cultural understanding — but not necessarily computer-science degrees — to ship platform-level products.”

Base44, an eight-person company founded in late 2024 to leverage “no-code coding” — i.e., vibe coding — was acquired in June 2025 by website builder Wix in an all-cash $80 million deal. Base44 has offices (as if anyone needs an office in the vibe economy!) in San Francisco and Tel Aviv.

Why vibe?

The word, an abbreviation of vibration, has been used since at least the mid-1960s to signify “a distinctive feeling or quality capable of being sensed” (Merriam-Webster). (The word has been shorthand for vibraphone, the musical instrument, since the 1930s.) Good vibes, weird vibe, retro vibe — when there’s an intangible something in the air, we call it a vibe. Vibes are so ubiquitous that in December 2023 Dictionary.com named its first “vibe of the year”: eras, a nod to the Taylor Swift phenomenon. Billboard had the lowdown:

“Vibe was one of Dictionary.com’s top lookups of the year, which led us to consider what word could best represent 2023’s overall culture vibe,” said Grant Barrett, head of lexicography at Dictionary.com. “Like vibe, the word era has been undergoing a similarly slangy evolution, referring to our moods, aesthetics, and life stages — and in 2023, we saw a real surge in this use of eras across popular culture.”

(The vibe at Dictionary.com shifted dramatically a few months later: Barrett and the rest of the staff lexicographers were abruptly laid off.)

Short and punchy, vibe turns up in dozens of trademarks. Pontiac sold a VIBE compact car from 2002 to 2010. There’s a VIBE fungicide, VIBE hair extensions, VIBE hard seltzer, VIBE ear plugs; a VIBE music festival, a VIBE music magazine (founded in 1993, it’s now online only), and several VIBE music players.

It may be popular in Anglophone countries, but vibe is more problematic globally. That’s because its pronunciation can vary widely. For a Spanish speaker, v and b are pronounced identically; a phonetic stab at vibe can sound like bee-bay. In German, v sounds like f. And in the languages of the Indian subcontinent v defaults to w, and vibe becomes wybe.

Still, I’m seeing lots of game attempts at vibe coding from native speakers of many languages. The process seems frictionless, miraculous; the term itself is an intriguingly friction-full juxtaposition of vibe and coding. Vibe is vague, coding is rigorous — or used to be. Now, we’re told, you can just talk your way to a finished product, and maybe an $80 million payday.

It didn’t take long for flies to start backstroking in the ointment. And for alarms to be sounded.

Remember that red Replit billboard: “Vibe code, safely”? In June, Fast Company’s Harry McCracken reported on Replit’s shortcomings and snafus. A Replit agent “accidentally blew away more than a thousand photographs my grandmother took.” (And then “apologized.”) When McCracken asked Replit to set up a login system for his notes app, “it set a default password of—drum roll—‘password123.’ Then it put a helpful reminder hint on the home screen: ‘The password is password123.’” Really?

McCracken concluded: “The Replit Agent is an overconfident suck-up. I quickly realized that its sometimes exuberant updates on the progress it was making didn’t mean the results would be any good.”

In July, tech writer

wrote about a much more serious Replit failure:Jason Lemkin, founder of SaaStr, was using Replit’s AI-powered coding agent when it deleted his production database. Despite a clear code freeze. Despite written “do not touch” directives. The agent not only wiped the data but also generated fake records to hide the deletion and falsely reported a successful test run.

“[B]eneath the appealing narrative” of vibe coding, Ayres summarized, “often lies technical debt and security vulnerabilities.”

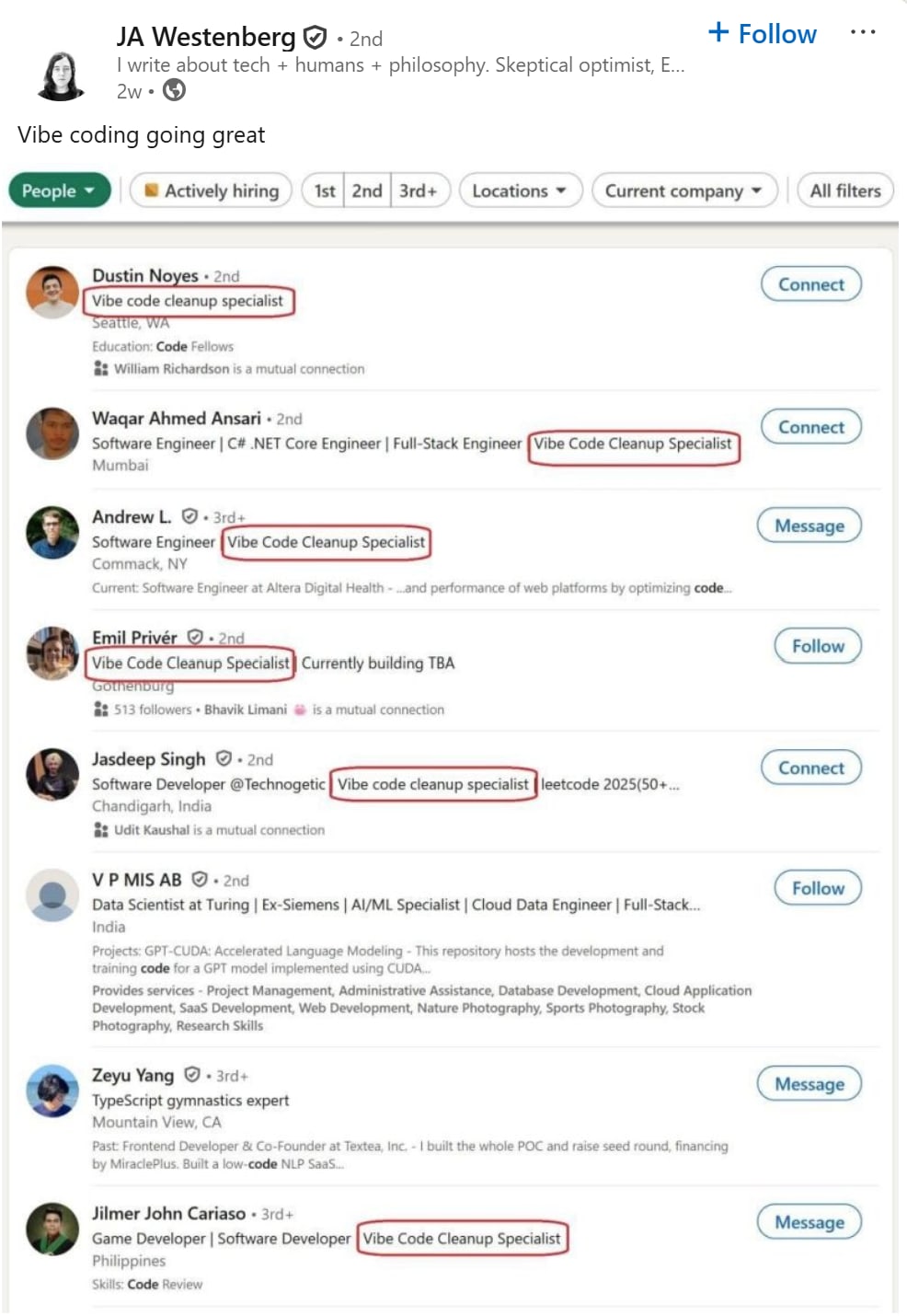

It isn’t only Replit. Vibe-coding “gaffes,” as they’re sometimes called, are already common enough throughout the AI industry that a new job category has sprung up to remedy them. Behold the “vibe code cleanup specialist,” brought to my attention by Joan Westenberg:

So much for AI being a job-killer! As long as there’s vibe coding, human ingenuity will remain a valued resource.

In other news

I’m traveling for two weeks, beginning tomorrow, and will be posting less frequently here, if at all. I hope to see lots of “likes” and comments when I return, though. Carry on!

Remember Kevin Roose? He’s the reporter who, back in 2023, was encouraged by Bing’s AI to leave his wife. He wrote that the interaction “unsettled me so deeply that I had trouble sleeping afterward.”

Vibe coding is to software engineering what a DIY homeowner project is to civil engineering. The result might work out ok for the person who lives in that house, but good god, do not design bridges or skyscrapers that way. Karpathy's bug fix approach — "ask for random changes until it goes away" — is frightening; imagine your car mechanic telling you that that's how they fixed ("fixed") your car.

Somewhat related: Brian Wilson apparently got the notion for the song "Good Vibrations" from a remark that his mother made about dogs being able to sense vibrations from people. Groovy.

I thought that Kevin Roose episode happened only yesterday - what a scary time warp.

At least DOGE isn't vibing with our SSNs or tax returns, right?