On November 9 G/O Media announced that it was pulling the plug on Jezebel, the 16-year-old feminist website that covered, as its tagline put it, sex, politics, and celebrity — ”with teeth.” Those teeth were what earned Jezebel its passionately loyal readership and also, it seems, what gnawed at advertisers obsessed with “brand safety.” Not that the corporate overlords were admitting it. G/O, which stands for “Get Out1,” laid off Jezebel’s 23 employees, invoking the usual “economic headwinds” as an excuse.

It’s quite a bit more complicated — and crass, and craven — than that, as 404 Media pointed out in a story headlined “Advertisers Don’t Want Sites Like Jezebel to Exist.” The nut graf: “The 'Brand Safety' and 'Suitability' industries have financially crushed the news business by keeping ads away from articles that its 'sentiment analysis' algorithms think will make people sad or upset.”

Or as journalist and capitalism critic Cory Doctorow put it: G/O Media is “unwilling to pay for a human salesforce that would — for example — sell advertising space on Jezebel to sex-toy companies or pro-abortion groups.”

I am here neither to praise Jezebel — I was never more than an occasional reader, although I was always impressed by the smart, often hilarious comments on posts — nor to bury it, which G/O has already done with ruthless efficiency. Instead, let’s talk about the long and complicated history of the “Jezebel” name.

Jezebel dot com

Jezebel the website launched in May 2007 as the “women’s vertical” of Gawker, the celebrity-and-media blog founded by Nick Denton. Denton had envisioned the new site as “a girly Gawker” to be called Celebutaunt, according to a 2017 Guardian article about how Jezebel “changed women’s media.” (“Celebutaunt” was a punning twist on “celebutante,” a portmanteau of celebrity and debutante that was first used in 1939 to describe that year’s It Girl, Brenda Frazier.) A Gawker lawyer proposed the name change to Jezebel; although founding editor Holmes “hated it for being too obvious,” according to The Guardian, it proved popular: “Commenters on the site started calling themselves ‘Jezzies’ and ‘Jezebelles.’” It was an example of what linguists call “reclaiming” or “reappropriating”: turning a slur (like, say, bitch or queer) into an affectionate epithet or even a badge of pride.

The first Jezebel

How did “Jezebel” come to be a slur? It’s a name steeped in notoriety, although its reputation may be at least partially unearned.

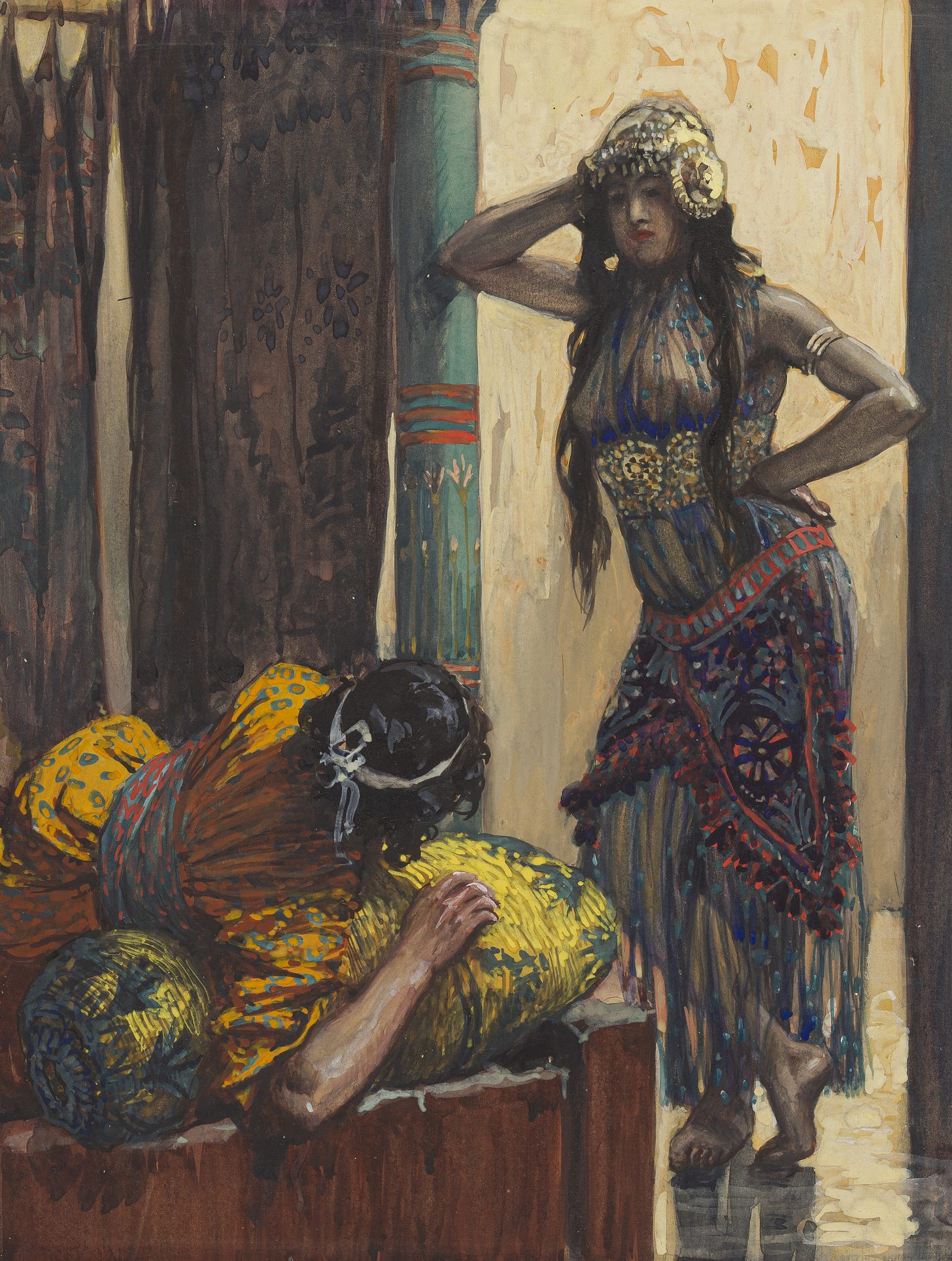

The story of the first Jezebel is told in 1 Kings and 2 Kings of the Hebrew Bible. She was the daughter of a Phoenician king who married Ahab, the seventh king of Israel in the mid-ninth century BCE. Ahab had multiple wives; Jezebel was the chief one and his co-regent, and the mother of the next king of Israel, Jehoram. Their marriage cemented an alliance between two rival kingdoms, but it wasn’t without its tensions. Jezebel worshipped Baal; Ahab worshiped the Hebrew god YHWH. Ahab may have been okay with the mixed marriage — he even built a temple to Baal in Samaria so Jezebel could worship there — but the Hebrew prophet Elijah definitely wasn’t. (Yes, this is the Elijah for whom we open a door during the Passover seder.) Elijah kills, or has killed, Jezebel’s Baal-worshipping prophets. Jezebel vows to kill Elijah in retaliation. Elijah flees. Jezebel, meanwhile, uses trickery and legal savvy to obtain property belonging to a man named Naboth, who is, alas, stoned to death. In the end, Jezebel is murdered — defenestrated, to be precise — by palace officials, and, in one of those charming Old Testament details, dogs eat her corpse.

The Jewish Women’s Archive does an admirable job of contextualizing the Jezebel story:

[T]here is no doubt that the biblical and later accounts distort her portrait for several reasons, among which we can list her monarchic power, deemed unfit in a woman; her reported devotion to the Baal and Asherah cult and her objection to Elijah and other prophets of YHWH; her education and legal know-how (shown in the Naboth affair); and her foreign origin. Ultimately, the same passages that disclaim Jezebel as evil, “whoring,” and immoral are witness to her power and the need to curb it.

Tl; dr: “[R]esentment of her can be at least partially attributed to the general scriptural dislike of powerful women.”

What does “Jezebel” mean?

“Jezebel” is the Anglicized version of the Hebrew איזבל (ʾIzeḇel), which The Oxford Guide to People & Places of the Bible says is “best understood as meaning 'Where is the Lord?’” (or, alternately, “Where is the Exalted One?”), which was “a ritual cry from worship ceremonies in honor of Baal during periods of the year when the god was considered to be in the underworld.” (Wikipedia)

Thus, if you come across a baby-name site that claims that Jezebel means “pure” or “virginal,,” or that Jezebel means “not exalted,” you may safely ignore it.

Also, Jezebel is not etymologically related to Isabelle, which comes from a different Hebrew source (“Elisheva”).

Jezebels everywhere

In both Old and New Testaments, Jezebel is associated with false prophets. (Revelation 2:20: “You tolerate that woman Jezebel, who calls herself a prophet.”) Over the centuries, Christians in particular began to associate her with sexual promiscuity and general immorality. The OED explains: “The story of her death, which she is said to have faced deliberately wearing fine clothes and make-up, probably reinforced these associations, since make-up was regarded as disreputable in some forms of Protestantism.” (“Painted” is the frequent modifier of “Jezebel.”)

By the 20th century, “Jezebel” had entered popular culture as either a synonym for “bad woman” or — in feminist retellings — a bold and powerful woman. In Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Jezebels are women who are sterilized and forced into prostitution. “Jezebel” is the subject of many popular and gospel songs, including Frankie Laine’s 1951 hit: “If ever the Devil was born without a pair of horns/It was you, Jezebel, it was you.”

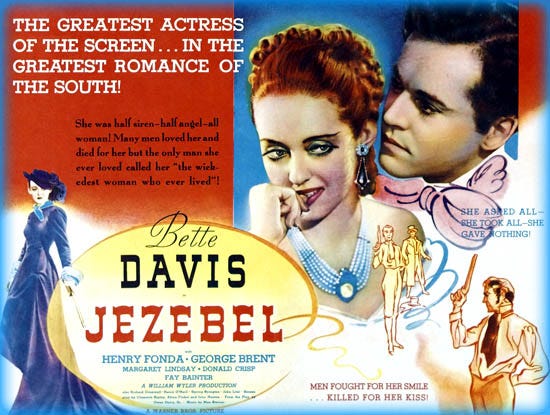

The most famous of the pop-culture Jezebels may be Bette Davis’s title character in Jezebel, the 1938 Southern epic that foreshadowed in several significant ways Gone with the Wind, which was released the following year. One of Jezebel’s taglines is “The story of a woman who was loved … when she should have been whipped!”, which reveals quite a lot about what passed for acceptable public banter back then.

Curiously, it took until March 2023 for Jezebel the website to review Jezebel the movie. “I was thoroughly, surprisingly, entertained throughout,” wrote senior editor Lauren Tousignant in a preamble to her live-blog. Less than two minutes into her viewing she reports: “A fancy man in a top hat says, ‘Julie will have plenty to drink at the party.’ I suspect Julie is our Jezebel.” But is she? Her sins include not curtsying, showing up at a party wearing her riding clothes, and attending the Olympus Ball in a red dress that manages to be shocking even though this is a black-and-white film. Tousignant concludes:

So, is Julie a Jezebel? Yes and no. I don’t believe Julie is a Jezebel in the way that everyone around her thinks she’s a Jezebel. But Julie’s definitely a little jezzy! In the fun, rebellious, society sucks and I give zero fucks kind of way. At least, she was like that until, again, she begged to go to the banished island with her dying ex. But also, she is a slave owner. So honestly, whether or not she is a Jezebel doesn’t matter, because she sucks.

And that, friends, was Jezebel on Jezebel. If you’d like to learn more about the publication’s history, I recommend the New Yorker essay “Jezebel and the Question of Women’s Anger,” published on November 4 (did she know what was coming down?) by founding editor Anna Holmes.

I was interested to see in the Name Grapher (https://namerology.com/baby-name-grapher/) that "Jezebel" as a girl's name gets zero hits. Assuming I did my search correctly, that suggests that in the US, at least, the name has been thoroughly pejorated.

Now I wonder if there are other such names, ones that have been so tainted that they're effectively off the list, so to speak.