Grift was among the most-looked-up words on Merriam-Webster.com last week, along with mother, habeas corpus, equalize, eighty-six, and dibble.1 I’ll leave the other words for another week’s research — “dibble” was completely new to me! — and turn for now to the world of cons and crimes.

It probably won’t surprise you that people were looking up grift because of Donald J. Trump’s thirsty acceptance of the Qatari government’s offer of a $400 million jet to be used as Air Force One, an offer the New York Times delicately described as raising “substantial ethical issues”:

“Even in a presidency defined by grift, this move is shocking,” said Robert Weissman, a co-president of Public Citizen, a consumer advocacy organization. “It makes clear that U.S. foreign policy under Donald Trump is up for sale.”

No biggie, said the former game-show host currently occupying in the White House. Only “a stupid person” would say “‘No, we don’t want a free, very expensive airplane,’” he explained.

Lest you think grift is a particular fixation of The Failing New York Times, the word has been appearing elsewhere as well, attached to the same short-fingered vulgarian. The May 13 episode of “Impromptu,” the Washington Post’s opinion podcast, was headlined “The Art of the Grift.” In his intro, host Dana Milbank catalogued some of “the president’s extravagant self-dealing” and wondered “whether there's anything anybody can or will do about it.” Other Post opinion columnists chimed in:

Molly Roberts: It just doesn't end. It’s just grift, graft everywhere you look. . . .

James Hohmann: It’s so easy to lose track of, like, there’s this deal and that deal, but that is the through line, graft and graft.

Grift and graft: related? Hold that thought.

Cartoonist Barry Blitt found visual expression for grift in a new illustration for The New Yorker.

Nor is the Trump-grift connection new news. It’s been a hot topic for months — indeed, years.

In “The Favoritism Grift” (The New Yorker, April 9, 2025), Nathan Heller wrote about nonmonetary forms of presidential corruption: “the more you give to some people while excoriating others, the more you can manage to take.”

In “The Donald Trump 2.0 Grift Is Already On” (Wired, January 20, 2025), David Gilbert documented the cash grabs that began on Inauguration Day — and their Trump 1.0 precedents: “Grifting and cash grabs in Trumpworld are nothing new. Ever since Trump came to office in 2016, he and his sycophantic supporters have embraced a wide variety of schemes. With Trump support, many figures have made entire careers grifting on topics like stolen elections or Covid denialism.”

And what about the Trump family’s various cryptocurrency and memecoin schemes? The Wall Street Journal was cautious about using the G-word in a May 11 editorial headlined “The Trump Family Crypto Business,” but the implication was clear: They raise “the appearance of a conflict of interest in selling access to the President.”

was less equivocal in an April 8 newsletter headlined “Trump’s chief gift is for grift”: “His ‘meme coin’ scam makes Watergate, Teapot Dome, Crédit Mobilier and all other White House scandals through history look like child’s play.”And let’s be clear: grifting is a crime. Here’s how the Criminal Defense Lawyer website puts it:

Grifters are often described as small-time lawbreakers who have a knack for swindling, tricking, and deceiving others, also known as “grifting.” Instead of stealing or taking something by force, grifters try to take others’ money or possessions the easy way—by convincing their victims to willingly hand it over.

But no matter what you call it, in legal terms, the act of grifting falls under the crimes of theft, larceny, swindling, or fraud. The exact crime will depend on how the state defines these crimes.

Grift is, it must be said, as American as apple pie and the Black Sox scandal. The word is U.S.-birthed slang for “one’s criminal occupation” (1914), “professional confidence trickery” (also 1914), and “the monetary proceeds of corruption” (1929). (Source: Green’s Dictionary of Slang.) It gained currency through the writings of Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and other detective novelists. (Raymond Chandler in Little Sister, 1949: “He had some kind of a grift, but he don’t have the looks or personality to bounce checks.”)

Grift was a twist on an older slang term with similar meanings: graft, which was also born in the U.S.A., around 1865. The original, more innocent graft had been around since the 15th century, and somehow its botanical sense of “fixing a shoot into another stock” found new life in another sort of fix: “the obtaining of profit or advantage by dishonest or shady means.” Graft was also popular in the U.K. underworld, where it had a slightly different meaning of “one’s criminal undertaking.” In the U.S., by contrast, graft tends to have fixed itself onto political or corporate malfeasance.

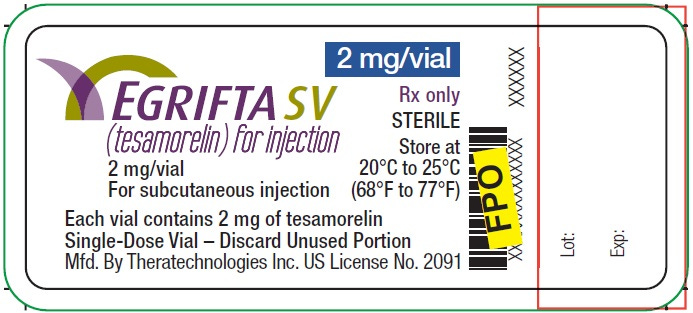

I first wrote about grift in 2012 (“The Grift That Keeps on Grifting”), when my attention was drawn not by a shameless party boss but by a pharmaceutical name. The journalist Andrew Sullivan had mentioned it in a blog post:

I am now on a new drug called Egrifta which targets HIV-related lipodystrophy, i.e. strange fat accumulation around your internal organs, by triggering an increase in your own body's production of growth hormone.

Egrifta is the brand name for tesamorelin, and it’s still for sale in an updated formulation.

I couldn’t find a story behind that peculiar name — no surprise, pharma names are as a rule deliberately opaque — but I did muse about possible taglines. The best one came from reader Dan Freiberg: “You take it. It takes you.”

It pains me to say that we’re all getting taken now by a gang of grifters with even more clout than Big Pharma.

Our pal the word genius claimed to have invented equalize: “So, basically, what we’re doing is equalizing. There’s a new word that I came up with, which I think is probably the best word, we’re going to equalize, where we’re all going to pay the same.” Merriam-Webster notes, deadpan, that equalize has been in use since the 16th century. According to the OED, its first appearance in print may have been in Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (1590). He spelled it equalise, of course.

It's not just an odd word, it's an odd sort of crime. I have always admired characters who could spot other people's weaknesses and talk them into things against their own interests, or pose as allies while robbing someone. We celebrate it when Bugs Bunny does it to Elmer Fudd, or the characters in The Sting do it to a gangster. But in our own lives, we have to admit that it's icky. In some ways it's worse than robbing people at gunpoint. If I took someone's money by fooling them, my father would come back from the grave to stand at the foot of my bed.

Loved this one and also the reminder to watch The Grifters. I have been enjoying movies from the late 80s, early 90s lately. I think there was something particularly great about films from that period.