The headline in The Baffler read “The Gigification of Publication.” And just like that, I heard music.

To my slight disappointment, the story, written by Dan Sinykin and published on March 18, turned out not to be about how book publishing is being transformed by a fictional young woman in Belle Epoque France whose female relatives are training her to become a courtesan. Au contraire: This gigification is lower case, pronounced with two “hard” Gs, and derived from gig, as in gig work and gig economy. But you will perhaps forgive my initial confusion. English pronunciation can bedevil even a native speaker like moi.

Here’s the second paragraph of Sinykin’s story:

You would be hard-pressed to find another trio who more cannily served the drive for growth in recent decades than the cofounders of Authors Equity, a new publishing house launched earlier this month. Authors Equity brings Silicon Valley–style startup disruption to the business of books. It has a tiny core staff, offloading its labor to a network of freelancers; it has angel investors, such as James Clear, author of the mega-bestselling self-help book Atomic Habits and the über-successful mystery writer and Hillary Clinton coauthor, Louise Penny; and it is upending the way that authors get paid, eschewing advances and offering a higher percentage of profits instead. It is worth watching because its team includes several of the most important publishing people of the twenty-first century. And if it works, it will offer a model for tightening the connection between book culture and capitalism, a leap forward for the forces of efficiency and the fantasies of frictionless markets, ushering in a world where literature succeeds if and only if it sells.

Further down, Sinykin writes:

Authors Equity’s website presents its vision in strikingly neoliberal corporatespeak. The company has four Core Principles: Aligned Incentives; Bespoke Teams; Flexibility and Transparency; and Long-Term Collaboration.

And what does “Bespoke Teams” mean? The term “is a euphemism for gigification. With a tiny initial staff of six, Authors Equity uses freelance workers to make books, unlike traditional publishers, which have many employees in many departments: editorial, marketing, sales, rights, production.”

Depending on your involvement with the publishing industry you may find this development a) alarming b) long overdue or c) inevitable. But let’s set aside those reactions, take a breath, and focus instead on that word gigification.

It’s a relatively new word for a phenomenon that’s been taking over our lives for more than a decade. I found several examples of gigification from 2019, including “The ‘gigification’ of work: Consideration of the challenges and opportunities,” by four professors at the University of Western Australia’s business school; and “How Gigification Is Reshaping the Concept of Careers,” from Interactive Workshops, a “design-led learning and facilitation company” with offices in London and New York. The Wiktionary entry — “the process hereby stable, fulltime jobs are replaced by freelance ones” — includes a citation from June 2020 about the effect of the Covid pandemic on “the gigification of knowledge work.” 1

Where did we get those gigs that are the components of gigification? Back in August 2015, in a Wall Street Journal column2 about the origins of “gig economy,” Ben Zimmer wrote that “the word ‘gig’ has long stumped etymologists”:

Before musicians got hold of it in the 1920s, “gig” had a number of slangy meanings, including “a trick,” “a joke,” or “a state of affairs.” It may be related to “gag,” which shared many of these same meanings, or may have emerged from an even earlier sense of “gig” as something that spins like a top (surviving in “whirligig”).

Another early sense of gig, which arose among 18th-century students at Eton College, was “an eccentric person; a fool.” Gig could also mean “a state of hilarity” or “a laughter-loving lass.” Around 1790, gig became the name of a lightweight two-wheeled carriage drawn by a single horse; the usage may have migrated from the “spinning/whirligig” sense or from the “laughter-loving lass” sense, since the carriage was considered suitable for young women.

Two additional observations about gigification:

First: New words built on the -ify and -ification suffixes have been popular, especially in brand language, for more than two decades. A British videogame developer claimed to have coined gamification — the enhancement of mundane activities through game techniques — back in 2002; it’s now seen everywhere. In 2010 PepsiCo’s CEO announced the company’s plans to “snackify” beverages and “drinkify” snacks. Clubification — privatizing public spaces — has been around since at least 2017, when it appeared in the international Journal of Urban Design; I recently saw “club-ifying” in a New Yorker article about restaurants that are switching to a members-only model. My colleague Christopher Johnson, aka The Name Inspector, traced the surge — or the “disturbifying trend,” as he called it — to Spotify, which was founded in 2006 and which may have inspired copycats like Shopify, Storify, and Zensify, ad infinitum. Lauren Michele Jackson wrote for the New Yorker in August 2023 about “the -ification of everything”; her examples included “old man-ification,” “NRA-ification,” “hoax-ification,” “popcraveification,” and of course “enshittification.” That last word, she wrote, “clarifies something about the suffix in question, which is that it rarely announces good news.”

And second: How do we know how to pronounce gigification if we’ve never heard it spoken? The G+vowel combination is notoriously tricky in English: We have girl and gift but also gibe and gist. Gimmick and gibberish. Giant (and gigantic!) and gigolo. (OK, the last one is a borrowing from French, whose pronunciation rules are a whole other species of mystification, but it’s thoroughly English now.) And maybe you’ve heard of the ginormous how-to-pronounce-gif controversy? (It’s gif as in gift. But that’s an arbitrary choice!) With gigification, we have an If You Know You Know situation. It’s possible that the pronunciation would be more transparent if the word were spelled gigafication — giga- as in gigabit — but then we’d lose the “gig economy” meaning.

As the King of Siam said: Is a puzzlement!

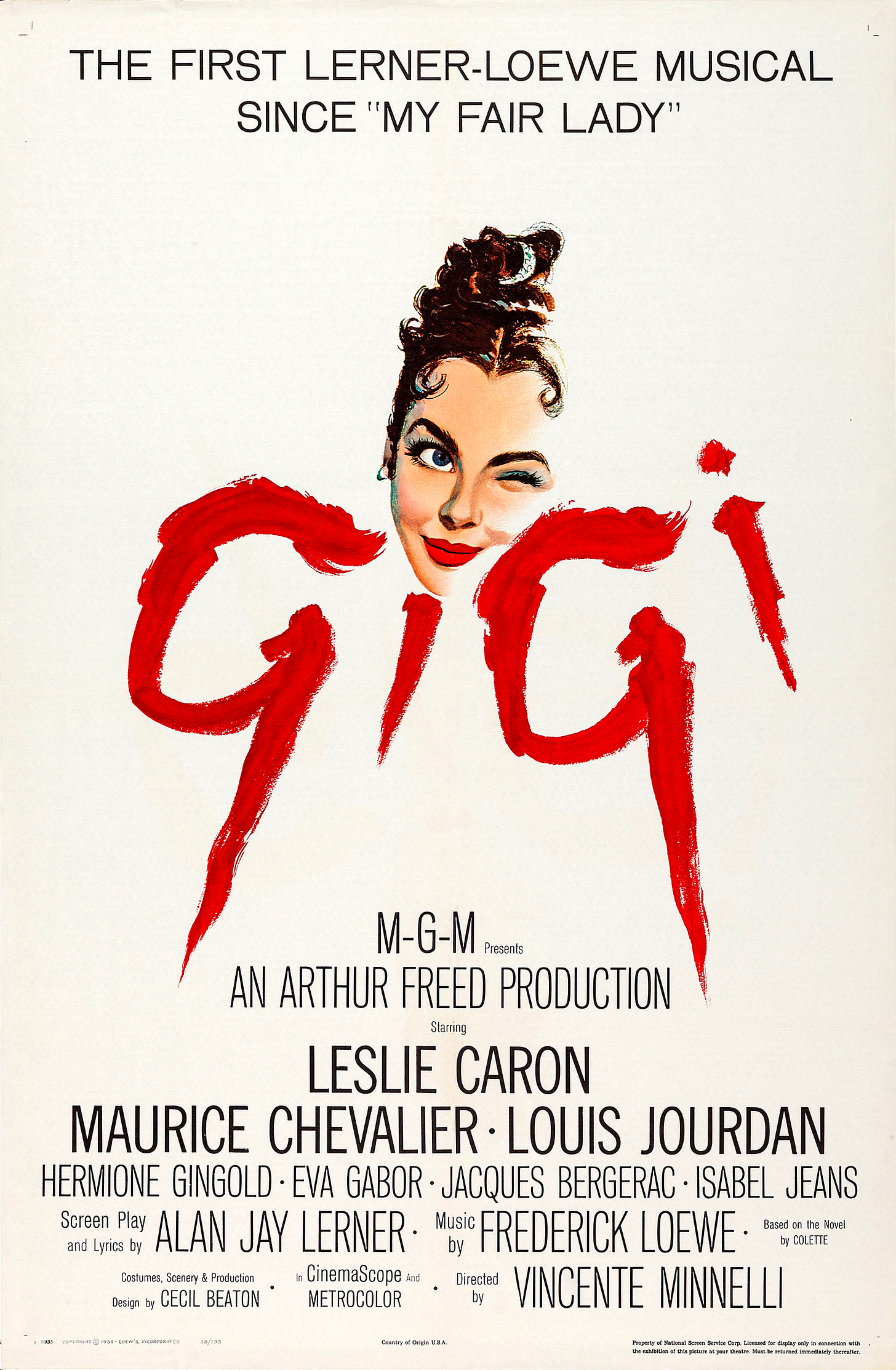

Yes, we’re back in musical-comedy-land! Did you know that the Gigi character’s full name is Gilberte? And that the surname of Frederick Loewe, the composer half of Lerner and Loewe, is pronounced “low” in English but “low-EV-ay” in Spanish? Good to know if you’re planning to plunk down several thousand dollars on one of those handbags from the Spanish luxury brand Loewe.3

And here, to wrap things up, is the title song from Gigi as sung by Louis Jourdan. The object of this adult man’s affection is a teenage girl, but the lyrics are so gorgeous I’m willing to overlook the ick:

While you were trembling on the brink

was I off yonder somewhere blink-

ing at a star?

Oh, Gigi —

have I been standing up too close or back too far?

Bonus: Spanish subtitles! Now, there’s a language whose orthography matches up nicely with pronunciation.

There’s a company called Gigify, based in Malta, that “connects GigWorkers with customers looking for help with with everyday chores and small jobs around the home.” Limited to Malta. Sorry!

Paywalled, with no gift links. Sorry!

Not even in my dreams.

Interesting to me that so many of these "-ify" words and names don't seem to double the final consonant in the way you might expect them to. Spotify isn't spelled like "spotty"; "clubified" isn't spelled like "clubbing"; etc. "Enshittification" seems to be the exception here. Not sure what to make of this!

An aside: gif is short for Graphic Interchange Format; hence, the hard "g" in gif (or GIF). At least, that's my take, and I'm sticking with it! :-)