Word of the week: Felon

In some quarters it's a badge of pride. That's one reason to be careful with the term.

In April 2019 The New Yorker published a Talk of the Town piece about a free Manhattan walking tour led by E. Jean Carroll, who at the time was known pretty much exclusively as the author of Elle magazine’s long-running advice column. The piece had been written by Lisa Birnbach — a famous advice-giver in her own right — and the walking tour was dubbed “Most Hideous Men of NYC.” Who qualified for the MHMoNYC title? A lot of characters you’ve probably heard of: Roger Ailes, Bill Cosby, Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, Bill O’Reilly, and, naturally, the most famous resident of Trump Tower.

At the end of her piece Birnbach noted that “Carroll plans to offer her ‘Hideous Men’ tours on the first and third Sundays of every month.” I gave a little whoop: I was headed to New York very soon and would be there on the third Sunday of May. I immediately booked my spot on the tour.

Which did not disappoint, although there was, in retrospect, a curious omission. In addition to the perps named in The New Yorker, Carroll — who wore a bright-red wig and was spirited, energetic, and often hilarious — guided us to the former haunts of rap mogul R. Kelly (serving a 31-year sentence for child sexual abuse), film producer Harvey Weinstein (in prison since February 2020 for felony sexual abuse), and TV presenter Charlie Rose (no prison time, but he was fired from CBS and PBS after multiple sexual-abuse allegations came to light).

But although our tour had begun at Bergdorf Goodman, on 5th Avenue and 58th Street, Carroll never mentioned her own fateful and unwelcome encounter in a dressing room there, in 1995 or 1996 (she was a little fuzzy on the date), with the future 45th president of the United States. She would publish her account of it almost exactly one month after our tour, in the June 21, 2019, issue of New York magazine. The upshot, as we know, was E. Jean Carroll v. Donald J. Trump, which resulted in Trump’s conviction in May 2023 on charges of sexual abuse and defamation. A year later, Trump was convicted on 34 felony counts of falsifying business records to cover up a hush-money payment he made to adult-film actor Stormy Daniels. Trump is also facing felony charges in three other cases.

All of which is a long preamble to this: Is it accurate to call Trump — the first former U.S. president to be found guilty of felony crimes — a “felon”? Is it a good idea to call him that?

And what about those other high-profile fellows in the headlines this week? New York City Mayor Eric Adams, 64, has been charged with bribery, wire fraud, conspiracy, and two counts of soliciting campaign contributions from foreign nationals. Rapper/producer Sean Combs, 55, aka Diddy, aka Puff Daddy, aka P. Diddy, is “accused of kidnapping, drugging and coercing women into sexual activities, sometimes through the use of firearms and threats of violence.”

They’re innocent until proven guilty, of course. But if that proof comes through will they be “felons”?

Well, yes, technically.

A felon, says Merriam-Webster (as well as other standard dictionaries), is a person who has committed a felony.1 And what is a felony? It’s “a grave crime” such as murder or rape or something else “involving forfeiture.” In many U.S. jurisdictions it’s a felony if the prison sentence is one year or longer, a misdemeanor if the sentence is less than one year.

We get felon and felony from the Anglo-French word felun, which meant “evil-doer” and which is related to fell, as in “one fell swoop.” (See Stan Carey’s article for Vocabulary.com for more about “one fell swoop.” Felon is not related to fellow, though. I wrote about fellow in 2019.) Merriam-Webster offers criminal, malefactor, lawbreaker, knave, and reprobate as synonyms, among many other similarly evil-tainted nouns.

No one knows how the word came into French; a long entry in the OED suggests a Latin source that meant “gall” or “someone or something that’s full of bitterness.” The Online Etymology Dictionary passes along a different theory, advanced by one Professor R. Atkinson of Dublin, that connects felon to Latin fellare “to suck,” “which had an obscene secondary meaning in classical Latin (well-known to readers of Martial and Catullus), which would make a felon etymologically a ‘cock-sucker’.”2

Hold that thought.

A curious thing has happened to felon in recent years, and especially since the Trump conviction in May: It’s been rehabilitated. Like its cellmates gangster, thug, and outlaw — all of which at one not-too-distant time conveyed strong condemnation — it has been drained of disapproval and even elevated to heroic status.3

In the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office database, for example, there are FELON trademarks for wine; for bicycles and bicycle parts; and for golf clubs that don’t conform to USGA rules (“But hey, golf is supposed to be fun isn’t it!” — Custom Golf Center).

The Sally Hansen cosmetics brand sells a nail polish called Watermelon Felon, a name that may have been chosen merely for the rhyme. And a brand called Righteous Felon sells meat snacks for humans and dogs; a “manifesto” on the website spins a fanciful tale about a “syndicated international jerky cartel” and quotes Nelson Mandela: “When a man is denied the right to live the life he believes in, he has no choice but to become an outlaw.”

It’s that Mandela-esque sentiment that drives the most conspicuous reframing of “felon”: as a partisan badge of honor.

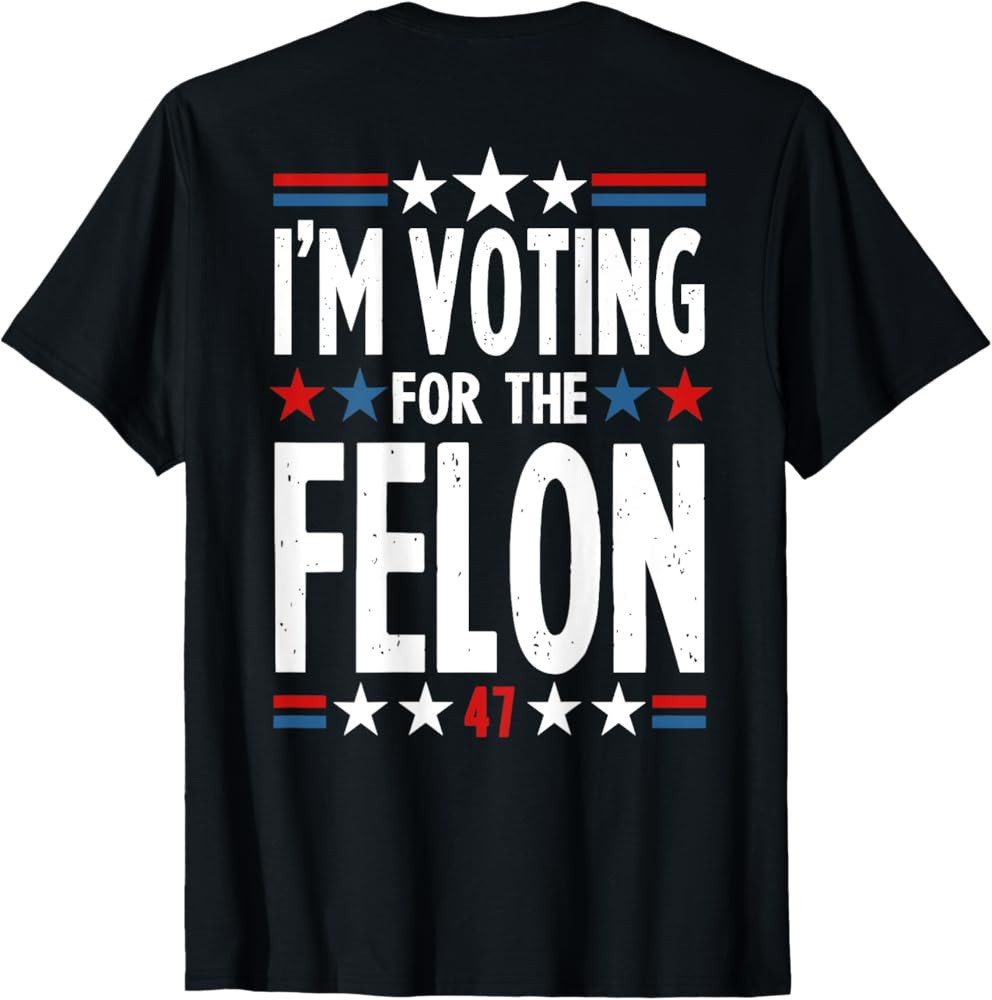

Search for “felon” + “shopping” and you’re served a Kmart’s worth of pro-Trump, pro-felon wares: “I’m Voting for the Felon” buttons, “Convicted Felon ’24” T-shirts, “Felon for President 2024” mugs — all this despite a warning from the Trump campaign that conviction profiteering was off limits. (There are also some “Prosecutor vs. Felon” products, a reference to Vice President Harris’s long career as a district attorney and California attorney general.)

One of the first felon-preneurs to jump on this bandwagon was 20-year-old Weston Imer of Colorado, who financed his trip to the Republican National Convention, in Milwaukee, by creating and hawking “I’m Voting for the Felon” T-shirts. “We all know that these charges were fabricated by the New York DA’s office and were elevated from misdemeanors to felonies just to ‘Get Trump,’” Imer told Colorado Politics in a text message.

So is Trump an actual felon or a persecuted victim? Make up your mind, sir!

Here we have two reclaimed slurs in one yard sign:

Yard signs and T-shirts are one thing, but Serious Journalism is another. The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization based in New York, cautioned in a July 25 analysis against calling the former president a felon, citing the latest edition of the Associated Press stylebook, “coincidentally released the day before Trump’s conviction,” which advises using “person-first language to describe someone who is incarcerated or someone in prison.”

“Trump has delayed and avoided judicial proceedings for much of his career,” wrote the Marshall Project’s Carroll Bogert:

Surely part of the impetus behind the sudden widespread use of the word “felon” is to take Trump down a peg, to label him as no better than a common criminal. And that is the problem.

Most people in prisons and jails in America come from lives of poverty and discrimination. A label such as “felon” or “inmate” contributes to keeping them at the margins of society. . . .

By calling Trump a “felon,” we risk rehabilitating a word that has fallen out of favor for good reason.

Trump is a person convicted of felonies. So are millions of other Americans. How we describe him affects them, too.

Very sound advice. Alternatively, you could default to E. Jean Carroll’s terminology and call TFG and other persons convicted of felonies Most Hideous Men. Or here’s a thought: You could cite history and etymology and call them cocksuckers. That couldn’t possibly offend anyone, could it?

A felon is also — and I had been blissfully unaware of this until just now — “a painful abscess of the deep tissues of the palmar surface of the fingertip that is typically caused by bacterial infection . . . and is marked by swelling and pain.” You may want to think twice about doing an image search.

I have not found any evidence that felon comes from Elon plus F.

For gangster, consider how “OG,” which was popularized by Ice-T’s 1991 album “O.G. Original Gangster,” now means “original and highly respected.” Outlaw has been losing its edge since the mid-1970s rise of “outlaw country” music; its perpetrators — Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, et al. — weren’t actually breaking any laws; they were just out of the mainstream. As for thug — from Hindi thuggee, a swindler, and later “a violent criminal” — it has evolved into something closer to “street-smart individual.” There have been many “Thug Life” song and movie titles, and Thug Kitchen, a plant-based, profanity-laced recipe site, was launched in 2012 by a couple of white cooks; the name was intended “to signal our brand’s grit in the otherwise polished an elitist food scene.” There were protests about the name, more for its racial overtones than its criminal associations. The name was finally changed in 2020 to Bad Manners.

You may have outdone yourself with this post, Nancy. Good stuff!

Wonderful!