Have you been thinking about death lately? Your own, perhaps, but maybe also or instead other deaths — the demise, say, on our watch, of institutions, of democracy, of the rule of law, of the planet? Are you wondering whether Mark Twain actually wrote “I have never killed anyone, but I have read some obituary notices with great satisfaction”? (He didn’t: It was Clarence Darrow.)

No? Just me? Well, too bad. You’ve come this far; now you’re going to follow me on a Stygian voyage.

A watery reference is apt here, because I’m finally giving myself permission to talk about aquamation, a word I first encountered three years ago and was reminded of just last week.

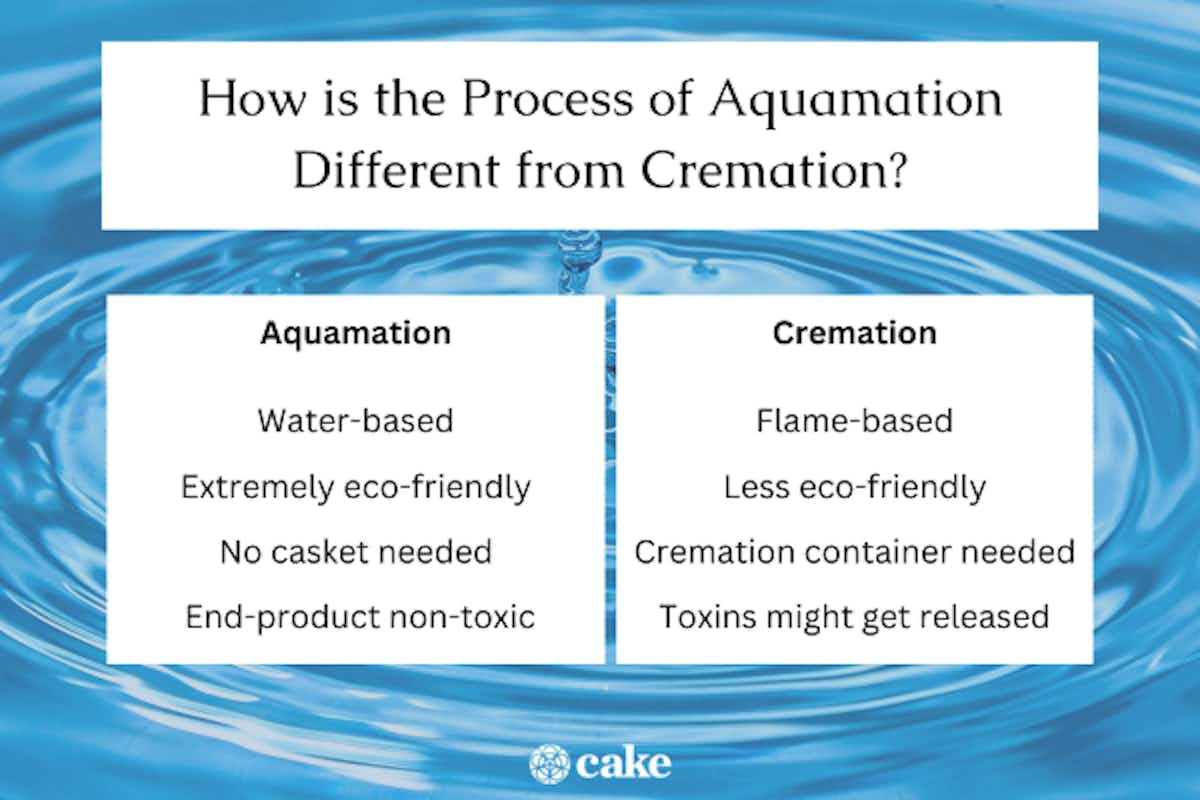

Aquamation, an attempted blend of aqua and cremation, is a marketing term for a scientific process called alkaline hydrolysis. It’s “a gentle process that uses water instead of fire to return a body back to Mother Nature,” according to Bio-Response Solutions, a Danville, Indiana–based company that offers capital-A Aquamation systems that “are changing the funeral profession.” (The gentleness is presumably to soothe the consciences of the living, not the tissues of the deceased.) Aquamation is what the body of Archbishop Desmond Tutu underwent in 2022, which is when I first became aware of the word and the procedure.

Here’s how the Guardian explained aquamation in its article about Tutu:

With aquamation, or “alkaline hydrolysis”, the body of the deceased is immersed for three to four hours in a mixture of water and a strong alkali, such as potassium hydroxide, in a pressurised metal cylinder and heated to around 150C. The process liquifies [sic] everything except for the bones, which are then dried in an oven and reduced to white dust, placed in an urn and handed to relatives.

In some U.S. states, aquamation is also an option for the disposal of pet remains.

Last week a Bay Area newspaper, the Mercury News, jogged my memory about aquamation with a profile of Francisco Rivero, a funeral director in the East Bay city of Emeryville whose company, Pacific Interment, specializes in water-based interment (inaquament?).

The profile provides some historical context:

Though it has only been available to funeral homes in California since 2022, the concept of cremation by water actually stretches back to the 19th century. A pioneering version of the process was patented by Amos Herbert Hobson, a British farmer who had immigrated to the U.S., in 1888 as a way to turn animal carcasses into plant food to keep them from polluting the environment and spreading disease. The modern-day take on an alkaline hydrolysis system for human cadavers arrived in 2005 when one was installed at the Mayo Clinic.

Rivero calls it “unbirthing”: “You come in water, you’re leaving in water.”

Aquamation interests me not only because of my preoccupation with death but also because of the word’s linguistic properties. Hello — it’s yet another example of word-formation by rebracketing, which we talked about last week in the forestalgia post.

Aquamation — the aqua part means “water,” obviously — was formed in imitation of cremation, a word we’ve had in English since the 1620s. (The verb to cremate is much more recent: It was introduced in 1851.) But the imitation is based on a false understanding of cremation’s formation: It isn’t [cre] + [mation] but rather [crema] + [tion]. The crema part comes from Latin cremāt, the participial stem of cremāre: to burn, to consume by fire.1 That’s why it’s cremat-orium (introduced into English in the 1880s) and not cre-torium2.

Around 1947, someone had the bright idea of calling the leftover products of cremation cremains. It’s a portmanteau of cremation and remains, and it probably contributed to our (false) impression that cre- is the historically and linguistically accurate prefix.

Whoever coined aquamation — I haven’t identified the inventor — clearly wanted to emphasized the similarity to cremation while also promoting the distinction. Carrying over the m from cremation drives home the similarity. (And -mation suggests automation more strongly than -ation would.) Maintaining the m also makes aquamation easier to pronounce, even if the process itself isn’t yet widely accepted.

How unfamiliar is alkaline hydrolysis to the public at large? Pacific Interment, while touting aquamation as “cutting-edge” and “environmentally friendly,” gives the process a semantic dehydration: The website calls it “flameless cremation” — an oxymoron for the ages.

Here’s a fun fact I discovered while doing this research: Cerveza, the Spanish word for beer, is likely related to cremation via the Proto-Indo-European root *ker- “heat, fire.”

It’s -orium, not -torium. The Latin element signifies “a quality proper to the action accomplished by the agent.”

And I thought, based on the word 'claymation', that 'aquamation' was going to be about a new form of animation using water.

I am one of the early pioneers in water cremation and a co-inventor of an alkaline hydrolysis system that works. From 2009 to 2011, my former company, Cycled Life, had rights to the Bio-Response Solutions’ (“B.S.”) pet system. I learned about alkaline hydrolysis the hard way: losing lots of money after discovering B.S.’ technology does not work.

There is a video on our website with an interview of Jeff Edward, a former owner of a B.S. system, in which he shares some problems with the B.S.’ Aquamation® systems: https://firelesscremation.com/human-pet-alkaline-hydrolysis-systems.

Here is some information on our patented system:

Laboratories, veterinarians, or funeral homes can use the FC-600 system. The process is similar for all three.

Alkaline hydrolysis systems typically require over 300 gallons of water per cycle. The FC-600 automatically adds water equal to 60% of the decedent’s weight, including water in the 45% potassium hydroxide. The rinse cycles use @18 gallons of water. For a decedent weighing 150 pounds, our system would use less than 10% of the total required by most other systems.

One can now offer families four new final disposition options since the non-bone remains weigh about 2x the decedent’s weight, compared to other systems that yield over 300 gallons of effluent per cycle. About half the families that my funeral home served opted to receive 100% of the “body” back. This enabled the body to be buried without a coffin or cemetery plot and sold as an Aqua Burial.

Ethanol (denatured alcohol) breaks down the long fatty chains. Water and alkaline do not. After a B.S. cycle, the top of their effluent forms a thick fatty layer. Unbroken fats are not beneficial to farmers. A fatty layer does not rise to the surface of our essence.

Below is a description from start to finish of an FC-600 cycle.

1. The decedent is lowered directly into the main vessel via a mortuary lift (no scissor lift required as is recommended with a B.S. or Resomation® system). We do not use a basket to hold the body. The body rests on the bottom of the system. After loading the body, the operator can safely remove clothing, open a viscera bag, and remove a body bag or sheet. Once the body is inside the vessel, there is no longer a risk of contamination or fall risks owing to fluids dripping onto surfaces. There is no minimum weight load requirement. However, if the body weighs less than 115 pounds, the system will add fluids as if the weight were 115 lbs. The FC-600’s maximum capacity is a 500-pound decedent.

2. When working with a medical or donor facility, you could process multiple remains simultaneously. You would place the remains in polypropylene bags, similar to how the FC-600 performs communal, separated, private dog and cat water cremations. This is a link to a video of pets receiving private, communal separated water cremations: https://photos.app.goo.gl/NmxLwuiUxRfecapi8. You would handle body parts in the same manner. Notice in this video, https://photos.app.goo.gl/KAsRSMNakkZQPopYA, the hollow bones — there is no marrow remaining, as there is with other systems.

3. The operator closes the latches on the vessel, then goes to the control panel and starts the process. Unlike the B.S. system, no tipping is required. Operators can go about their day since the system autocompletes the dissolution.

4. The time required to add chemicals is based on the deceased’s weight: 5-20 minutes to add the 45% potassium hydroxide, water, and ethanol.

5. The time required to reach the operating temperature, 160F, varies based on the deceased’s weight, body temperature, chemicals, and water; typically, it takes 30 minutes.

6. The dissolution cycle runs for a minimum of 2.5 hours for bodies weighing less than 150 pounds. For bodies weighing over 150 pounds, each additional pound adds one minute to a maximum dissolution cycle of 240 minutes.

7. After the dissolution cycle, a pump transfers the essence into the neutralization station. This step takes 5-15 minutes.

8. Rinsing the bones and the system takes about 20 minutes and uses 18 gallons of water. Our system uses 90% less water than other alkaline hydrolysis systems.

9. Removing the bones and medical implants takes about 5 minutes. A dustpan and brush easily remove the bones from the bottom of the system. As you experienced, the B.S. systems are infamous for having brains remaining within the skull, tissue on the vertebrate, sinews clinging to baskets, marrow, and long-chain fats. This is a video of bones being removed from the FC-500, not the new FC-600: https://photos.app.goo.gl/tX8EE32aLuVzBYoQ6. The FC-600 does not have a screen. You can see how easy it is to remove all the bones and prevent cross-contamination.

10. The system is available to start a new cycle. The total dissolution time for bodies under 150 pounds is about 3-3.5 hours and about 5.5 hours for decedents weighing 500 pounds.

11. Optional neutralization process: The neutralization of the essence takes place in the neutralization station. Glacial acetic acid is slowly metered into a tube of circulating essence (similar to a drip IV). This process reduces the release of vapors. The bubbles disappear before the fluid goes back to the neutralization tank. Adjusting the pH level of the essence to meet local water treatment facilities’ pH limits or for land application is easy to achieve. We would never use carbon dioxide or citric acid to lower the pH. Some acids mixed with the base liquid form hazardous vapors. Acetic acid turns the essence into a natural organic soil amendment. This enables families to choose an Aqua Compost or an Aqua Burial.

12. A hose with a nozzle provides a final manual rinse if desired.

13. The bones go into a dehydrator for 5-12 hours. If using a convection oven, the time will vary based on the heat setting and airflow. Depending on the ambient conditions of the facility, bones can be air-dried. The time required to air-dry bones could take 18-48+ hours.

14. Dried bones are ready to be processed and placed in an urn. This process takes 5-15 minutes, depending on the processor’s speed and power.

15. The neutralized essence is emptied into the sewer or a holding tank. The time required to empty the neutralization vessel is 5 to 15 minutes. For an Aqua Burial, Aqua Burial at Sea, or Aqua Compost, the operator would fill five-gallon plastic containers with the person’s essence. This step takes 10-15 minutes.

16. If desired, manually rinsing the neutralization station takes a few minutes.

Ethanol breaks down the triglyceride esters. Systems using only water and alkali form a fatty layer on the surface of cooled effluent, plus a fatty film on the system’s interior and baskets. Ethanol is key to our patented process. It significantly reduces the cycle time by breaking down the fats so the alkali can break down the proteins.

This video shows the bone remains at the end of a human process: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rDUxsLDjzehGqvRrIreYShHYcA80Urmd/view?usp=sharing.

Our heaters are external to the main vessel. The B.S. Aquamation® systems use internal heaters, which eventually fail because of exposure to the alkali.

Here is a link to information on the explosion and destruction caused by the B.S.’ high-temperature system: https://chipfm.com/en/Explosion-at-Hayes-Funeral-Home-in-Shawville.

Low-temp systems are much safer; however, using just water and alkali does not work. In 2011, I closed my company, which had licensed technology from B.S., after discovering that four out of nine bodies still had brains in their skulls after 18-20 hours in the Aquamation® system. I could not believe B.S. was still selling systems. In 2019, I assembled and invested in a team of biochemists and former rocket engineers to see if we could solve all the problems with

Aquamation®. We did! The FC-600 is our fourth-generation alkaline hydrolysis system.

Our essence is sterile, which would not likely be the case with effluent if the bones still contained marrow or brains remained in the skull. Our system destroys all pathogens.

No one who has taken our alkaline hydrolysis $1,500 Challenge Scorecard Challenge has ever bought another system from B.S. or Resomation®. Visit our website for more details on the $1,500 Challenge.

Maintenance requirements are expected to be minimal. The main stainless-steel vessels should last “forever.” Pumps, heaters, and actuators should last many years. The pH meter must be replaced every year or so and calibrated periodically.

Customers would need a barrel dolly to move the chemical drums, possibly an explosion-proof fan and ductwork (@$3,000 for equipment and installation), personal protective equipment (@$200), miscellaneous items (hose, dust pan, cookie sheets (@$200), and electrical power to the system. No costly 3-phase power as the B.S. system requires (cost site-specific).

Here is a link to a news story about an FC-600 water cremation system customer: https://www.wbaltv.com/article/water-cremation-alkaline-hydrolysis-system-baltimore/62911100. The customer mentioned a million-dollar investment, but he was referring to the entire facility, not the cost of the system.

More information at www.firelesscremation.com