If you followed U.S. politics even a little bit during the last few weeks, you would have been hard pressed to escape these two words.

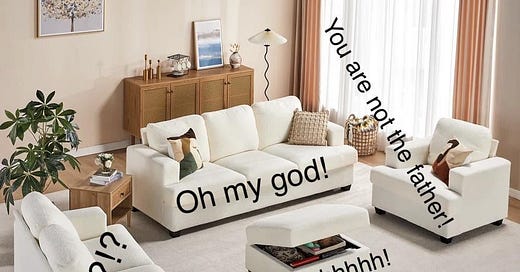

I’ll get to weird in a moment. First, though, let’s talk about couch, a word that’s become weirdly attached to Republican vice-presidential candidate JD Vance. The question: Did he or didn’t he? Head over to Strong Language, the sweary blog about swearing, to read my new post about couch-fucker and meet some other -fuckers, including windfucker (a bird of prey) and ratfucker (a Nixonian compliment).

For more on the etymology of couch, check out John Kelly’s August 2 blog post. Did you know that it’s derived from the Latin verb collocāre, “to place, arrange”? I didn’t.

John is a fellow contributor to Strong Language and the former vice president of editorial at Dictionary.com, which in April laid off all of its lexicographers, including John. Their loss — and it is a sad one — is the blogosphere’s gain. Welcome back, John!

As for weird’s rise in the polls, credit is due to Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, a Democrat who’s been on the shortlist of VP Kamala Harris’s potential VPs. On July 23 Walz gave a succinct summation of the MAGA standard-bearers: “These guys are weird.” Two days later, Harris’s rapid response team posted a “Statement on a 78-year-old Criminal’s Fox News Appearance” — the criminal in question was, of course, The Former Guy — that included a bulleted list of “main takeaways.” Takeaway #7: “Trump is old and quite weird?” The punctuation seemed to indicate can-you-fucking-believe-this rather than question-demanding-an-answer.

TFG’s running mate, He Who Has Been Associated with Carnal Knowledge of Upholstered Furniture, did not escape the indictment. On July 26 the Harris campaign issued a separate press release whose first sentence was “JD Vance is weird.”

Ben Zimmer, the Wall Street Journal’s language columnist, examined weird in his July 31 column (unlocked), noting that although the word “is being used as a pithy label to describe opinions or behavior considered creepy or bizarre,” “that meaning is relatively new in the word’s history”:

The origin of “weird” is in the Old English word “wyrd,” a noun meaning “fate” or “destiny” that appeared in some of the earliest Anglo-Saxon written records. After the Norman Conquest in 1066, classical learning became highly prized, and the word “wyrd” got applied to the Fates from Greek and Roman mythology, personified as three sisters who ensured that humans lived out their destinies.

Shakespeare called his three witches in Macbeth “weird sisters,” and because the witches’ supernatural powers “seemed mysterious and uncanny,” Zimmer writes, “the semantics of ‘weird’ moved in that direction.”

As for the spelling of weird, people have been getting it wrong —usually as wierd, because they learned “i before e” — for centuries. (People have been misspelling my i-before-e surname for almost as long.)

The contemporary “bizarre” meaning of weird was firmly in place when I wrote about it in November 2020, reflecting on that weird pandemic year:

It’s been a weird year for movies, for birding, for gamers, for football, for holidays, for our sense of geography. People have been reporting weird pandemic dreams. A lot of COVID symptoms are “weird as hell.” A whole subset of Trump-involved phenomena have been labeled weird in 2020: his dancing, his nominating convention, his “joke” about the true authorship of a New York Times op-ed bylined “Anonymous.”

In October, scientists reported discovering a weird molecule on Titan, one of Saturn’s “already weird” moons. A weird, glowing ball was spotted hovering over a forest in Mexico. The Chevy Bolt recall was “a weird one.” There’s something “super weird” about Netflix anime. Elon Musk posted some weird tweets and gave his baby a weird name, the unpronounceable “X Æ A-12.”

Weird may have subsided along with the worst of Covid, but it never completely vanished. The Democrats’ use of weird in the 2024 campaign cycle, wrote Jay Caspian Kang in The New Yorker, has “tapped into a great sense of relief among liberals”:

Weird is a catchall insult that allows liberals to slap back at years of similar aspersions from the right—connected to everything from trans rights to racial justice and abortion rights—and to normalize their personal politics through the imagined average voter, who, through this verbal sleight of hand, is now on their side. When it’s deployed by Walz, even someone like me—an Asian American who works in the media and lives in liberal Berkeley, California—can feel some purchase in a mainstream that values broadly popular policies such as abortion rights, free school lunches for all kids, or, really, whatever you want to slot in there. Its vagueness is its strength—any cause can be average—which is why it has lately been beat into the ground by every liberal politician within spitting distance of a microphone.

Moreover, writes A.R. Moxon in his newsletter, “The Reframe”:

What saying “weird” means in this context is that it’s normal to want government to help people, and it is abnormal to want it to harm people. It's normal to be part of and to celebrate an ever-increasing diversity of identity, and it’s abnormal to want to control and define everyone else’s identity. And, crucially, it is dismissive of supremacy. It says to supremacists. “If you are going to behave in such a topsy-turvy and indecent manner, I will oppose you, but I will not take you seriously.”

One last weird language note: Weird has been used as a verb since about 1300; it originally meant “to preordain by the decree of fate; esp. in passive to be destined or divinely appointed to, into, or unto” (OED). By 1970 instances of weirded out were being recorded in print; Green’s Dictionary of Slang includes three separate meanings for the term (to horrify; to experience or cause to experience hallucinations; to feel or cause to feel confused or at a loss).

I cannot think of a better example of “verbing weirds language.”

The upside of "weird" to portray Republicans: The media can no longer use "polarization" to define some fanciful political spectrum, with extremes at either end. Empathetic "Liberals" are now normal. Republicans are mean, pathological, and hate-filled liars.