The plus side of "plus-size"

Fashion vocabulary for bigger bodies

A pause to celebrate: Yesterday this newsletter crossed the 300-subscriber mark. I’m grateful to all of you and especially to those who made pledges of support. If you’re new to Fritinancy, here’s an explanation of the newsletter’s name and here’s a post about why I moved my blog to Substack. I write mostly about names, brands, and language — I wrote recently about my words of the year and my names of the year — but occasionally I take a detour into an area that just interests me, like movies or fashion. Don’t forget to check out the Notes tab for my quick takes and restacks.

I’ve been interested in the clothing category called “plus-size” for years. (See this 2015 blog post, for example.) I’m not a target customer — I wear what’s called “straight sizes.” (More about that term in a bit.) But it’s been impossible not to notice the increasing importance of “plus” in retail1. It’s a fashion story, a financial story, and a political story.

Last autumn two events neatly coincided to bring my attention back to “plus-size.” One was the death, on September 8, of Alexandra Waldman, founder of the Universal Standard brand and “an icon of the size-inclusivity movement,” as Fast Company put it.

The second was the release of a terrific episode, “Plus Sizes,” on the always-excellent Articles of Interest podcast, in which host Avery Trufelman explores some surprising corners of the clothing universe. (Like, say, prison uniforms.) Trufelman doesn’t mention Alexandra Waldman, but she does spend quite a bit of time discussing a brand I’d (ironically) forgotten all about and which for a time made a huge impact on the plus-size market: The Forgotten Woman.

So let’s consider those two brand names — Universal Standard, which is still around; and The Forgotten Woman, which isn’t, alas — and the language we use to describe their merchandise.

First, though, we need to go back to the pioneer of larger-size women’s fashion in the U.S., Lane Bryant. (Also still around, although its catalog division is now called Woman Within, a name about which I have expressed skepticism.) Lane Bryant, founded in New York in 1904 as a maternity-clothing boutique, got its name as the result of an error: When founder Lena Himmelstein Bryant, a Jewish Lithuanian immigrant, opened her first bank account Lena was misspelled as Lane. (When she married a second time she kept her first husband’s surname.) Noticing an unmet need for clothing for larger yet non-pregnant women, Lane Bryant introduced what the company called “misses-plus” sizes. They weren’t quite what we expect today: A 1922 ad in the New York Times boasted that the fashions “[solved] the heretofore unattempted problem of creating fashions, ready to put on, for the woman of smaller stature and fuller figure.” Five years later, Lane Bryant dropped the “misses” from “misses-plus,” but continued to use other terms, like “stout” and “chubbies,” for several decades.2 The “smaller stature” angle eventually disappeared. .

(In the UK, by the way, clothing for larger women was customarily called “outsize.” And clothing for large men in the U.S. has never needed to hide behind flattery or euphemisms: Just go ahead and say “big and tall.,” as JC Penney, Macy’s, and other retailers do — although some guys think it’s a misnomer. Boys with a few extra pounds get to shop in the “husky” department, availing themselves of a word that originally meant “tough and strong like corn husks.”3)

What do you call women’s clothing that isn’t “plus” or some other subcategory like “petite”? The industry term is straight. I have yet to see a dictionary entry for this sense of straight, which generally covers even sizes 04 to 16, although Collins Dictionary includes it among its reader submissions. This is straight not as in “curveless” but as in conventional: the same straight that’s the counterpart of gay or queer.

Lane Bryant may have forged new business territory but it wasn’t known for glamour or chic. Enter Nancye Radmin (1938-2020), who wore a size 16 after gaining 80 pounds during two pregnancies. She “was shocked to find that there were only polyester pants and boxy sweaters in her size” when she went shopping, as her New York Times obituary put it. “Fat,” she told Newsweek in 1991, “is the F-word of fashion.”

Radmin borrowed $10,000 from her husband, who was in the kosher meat business, and in 1977 opened her first boutique, on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. The Times obit said the store’s name, The Forgotten Woman, “was a reference to her clientele, women who wore sizes larger than most fashion designers manufactured, and perhaps, too, to the culture that overlooked them.” Outfits could cost over $1,000—in 1980s dollars—and The Forgotten Woman refused to accept returns. (“I don’t sell used goods,” Radmin said in 1989.) Eventually there were 25 stores around the U.S.—including one on Beverly Hills’s Rodeo Drive—and even a partnership with Vogue Patterns for home seamstresses who admired The Forgotten Woman’s high style but couldn’t afford the high prices. The patterns came in sizes 14 to 30.

As a brand name, The Forgotten Woman was bold but also a little forlorn. Surely the customer would have wanted to be known as a remembered woman, yes? Yet it wasn’t the name that doomed the company. Radmin sold a portion of the company to venture capitalists in 1989 and stepped down as president in 1991. The company filed for bankruptcy protection in 1998, and by the end of the year all the stores had closed. Beware the VCs and the hedge-fund bros, is what I say.

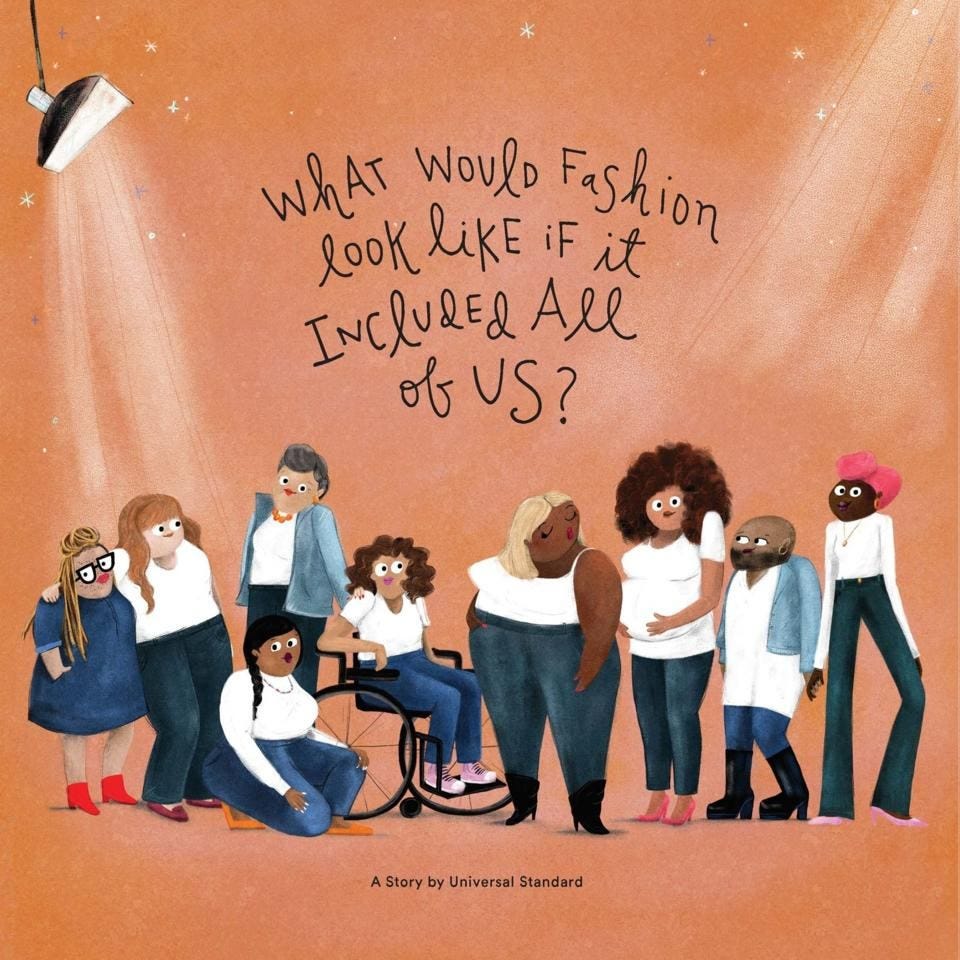

By the time of Radmin’s death in 2020 a new front had emerged in the size campaigns: “Inclusivity.” That was the banner under which Alexandra Waldman and Polina Veksler founded Universal Standard in 2015. Their first collection included just eight pieces in sizes 10 to 28; it now includes luxury clothing (through its acquisition of the Henning brand), outerwear, underwear, and swimwear.

Significantly, Universal Standard doesn’t brand itself as a large-size specialist. Instead, its “size inclusivity” now spans the spectrum from 00 to 40, or 4XS to 4XL. (According to Universal Standard, I would wear a 2XS, which translates here—but nowhere else in the retail world—to 6-8.. The “average” American woman wears size 16 to 18; according to recent Centers for Disease Control figures, 41.9 percent of the American population is obese—although we’re now supposed to say “living with obesity,” aren’t we? More like a companion than a condition.)

Universal Standard’s name proclaims its mission. Unlike “Lane Bryant” (discreet/Anglo) or “The Forgotten Woman” (romantic/tragic) — or other plus-size brands like The Limited’s “Eloquii” (which could have been a pharmaceutical name) and Torrid (which says “We’re hot!”) — Universal Standard is forthright and unembellished, much like its clothing. The “Our Story” page of the website reads like a political manifesto:

We’re the world’s most inclusive fashion brand, but access for all shouldn’t end with US. We want to change everything. We want to break barriers. We want to unite the divided. We’re committed to improving the industry standard by empowering everyone to embrace inclusion and working with partners who see it as we do.

Not for nothing, Universal Standard’s monogram is US. The company takes full advantage of the extra meaning: “You keep US inspired, and you keep US honest.”

What’s next in plus-size branding? The “Plus Size” episode of Articles of Interest suggests a pivot toward playful, fat-and-proud names: Plus Bus, Thick Thrift. It’s possible, though, that as people keep getting bigger “plus” will indeed become the universal standard, and the need to differentiate larger sizes will simply disappear. Plus will become straight, and we’ll all just go shopping together.

And also, unrelatedly, in streaming TV. See my 2021 story about all those + channels.

For more on Lane Bryant, see my 2015 post on the company’s “Plus Is Equal” ad campaign.

The dog breed husky is unrelated: It comes from the same root that gave us Eskimo.

The concept of zero — or even 00 or 000—as a clothing size is deeply weird, but beyond the scope of this newsletter.

No, we do not say “living with obesity”, and I strongly recommend Ragen Chastain’s Substack for info about why “obese” is such a problematic term and concept.

Also as someone who has always occupied a fat body, I can confirm that there’s little imminent likelihood of plus sizes becoming the norm and smaller ones being less common. Still very few brands sell larger clothing, and even when they say that they do, they don’t actually stock those sizes. Brands also had a few years of co-opting the body positivity movement, so instagramming pics of plus models in their clothes - but in reality not selling clothing in those sizes. And now ultra-thinness is back in, brands won’t bother with the body positivity bandwagon any more. TLDR, we fats had a brief moment of slightly more garment options, but not as many as you’d think, and the backlash is going to be harsh in our new era of semaglutides

You strike a chord in this enlightening piece. In the mid-90s, while editing Canada’s premier women’s magazine, I started using “plus-size” models (bit of a misnomer) and published a guide for fashion in tall, petite and plus sizes. To the dismay of the ad sales department, I once featured an array of real women with very real bodies on the cover. Readers loved this direction; higher-ups did not. My size is toward the small end of “straight” but I continue to feel for larger women who want stylish clothes they can afford.