Mavis Beacon

How "the Betty Crocker of software" got her name.

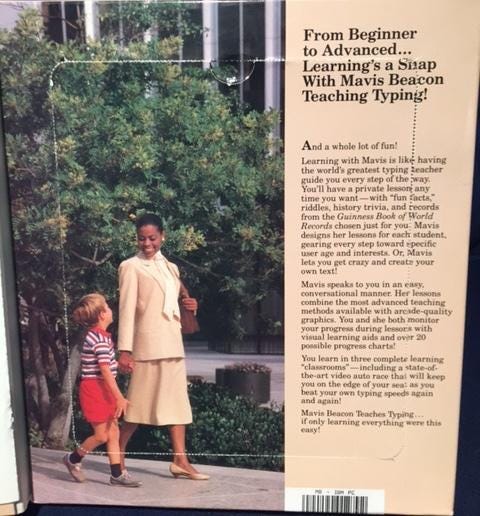

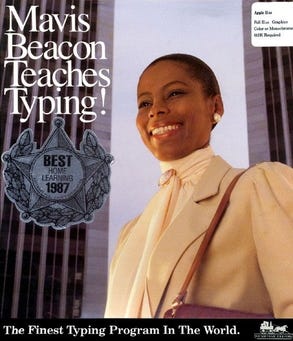

If you learned to type in the U.S. in the late 1980s or the 1990s, there’s a good chance you picked up your keyboard skills from Mavis Beacon, the smiling, crisply attired Black woman whose photo adorned the “Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing!” software package.

The program, first released in 1987 by a Sherman Oaks, California, company called The Software Toolworks, originally cost $39.95 for 5 ¼-inch disks, $44.95 for 3 ½-inch disks.1 “Of the many good typing programs available,” declared the New York Times’s Peter H. Lewis in a November 14, 1987, review, “Mavis is the best we’ve seen.”

He added: “I don't know how they teach typing elsewhere in the world, but I do know that Mavis is light years ahead of my high school typing commandant.”

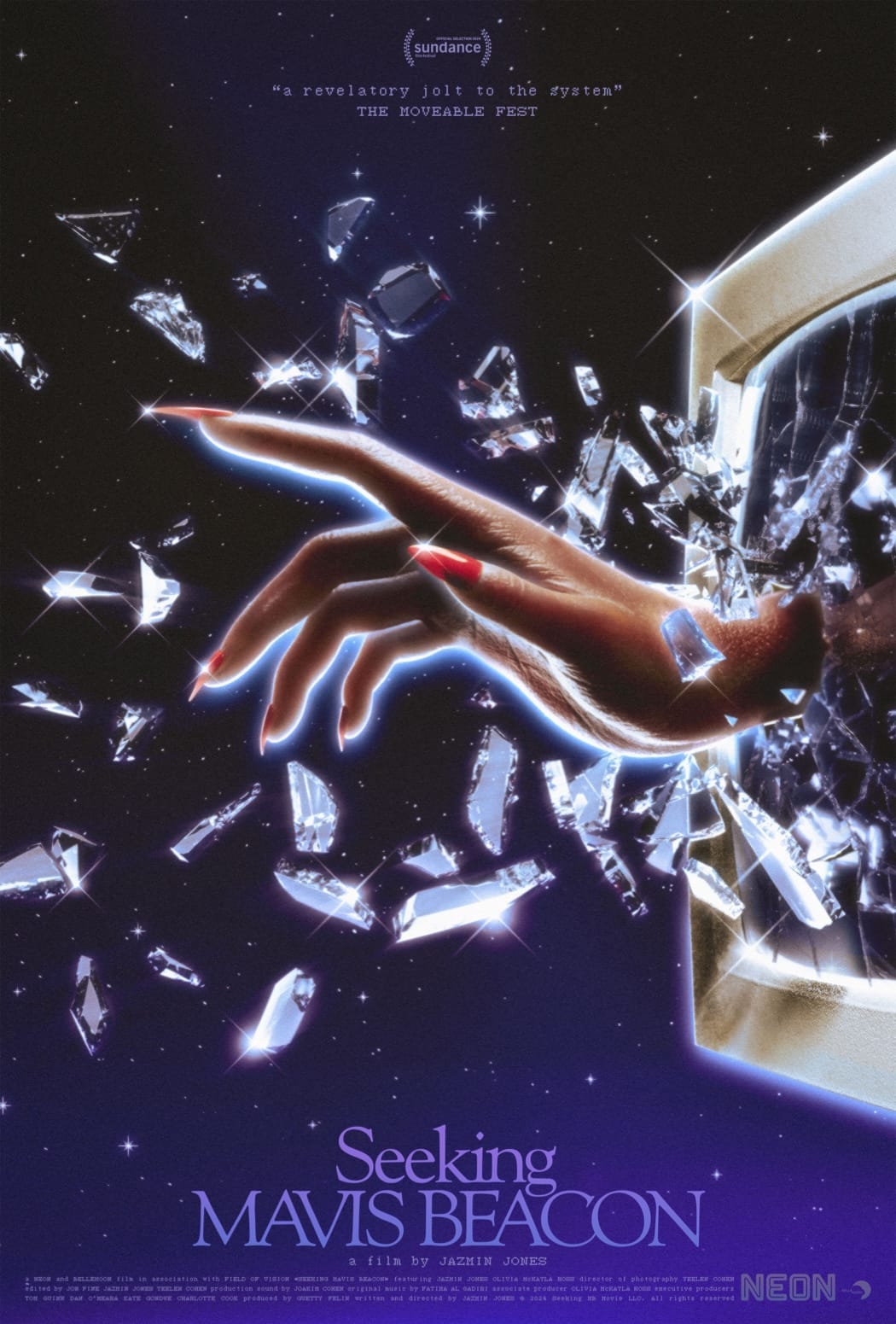

Lewis knew full well that “Mavis” was not a real person: In his third paragraph he disclosed that she was a fictional character. Her invented status, never a secret, would be confirmed over the years in published story after published story, and even in a Mavis Beacon fandom wiki. But that didn’t deter generations of fans from believing that Mavis was real.2 One of those fans was Jazmin Jones, who as a child learned typing from “Mavis” and who grew up to become a filmmaker whose new documentary, Seeking Mavis Beacon, attempts to sort fact from fiction and to answer questions about identity, representation, artificial intelligence, and internet privacy.

I saw Seeking Mavis Beacon in April at a San Francisco International Film Festival screening with Jones and her collaborator, Olivia McKayla Ross, in attendance. The film is now available to rent on Apple TV+ and other platforms.

But this is not going to be a film review. (Except for this: If you like your documentaries smooth and tidy, prepare to be disappointed. Seeking is highly personal, often messy, and inconclusive — but never boring. RogerEbert.com gave it three stars.)

Instead, I want to focus on two meaning-rich names: Mavis Beacon and Renée L’Espérance.

I’ve already introduced you to Mavis Beacon. Software Toolworks’ CEO, Les Crane (see Footnote 1), named the character after the Black gospel singer Mavis Staples — a favorite of his — and gave her a surname than signified “guiding light.”

Besides being a callback to Ms. Staples, “Mavis” has other noteworthy features. First, it’s an old-fashioned name: Its popularity in the U.S. peaked in the 1920s, according to the Namerology NameGrapher. (Mavis Staples was born in 1939. “Mavis” has enjoyed a bit of a revival in recent years, but nothing close to its 1920s heyday.) It’s also relatively unusual, never reaching higher than #279 in U.S. baby-name rankings. And it has a sweet history: An alternative name for a bird usually called a song thrush, mavis was adopted into English in the 14th century from an old French word, mauviz, that also was a bird name.

Beacon is an even older word, going back to Old English bēacen, which meant a signal or portent. It’s related to beckon: to summon or signal.

Whether any of this was intentional or not, to personal-computing early adopters in the late 1980s the Mavis Beacon name would have sounded both reassuringly traditional and intriguingly novel: neither as conservative as baking’s Betty Crocker nor as whimsical as Microsoft’s Clippy. The double-trochee stress pattern — MA-vis BEA-con — gave a subliminal suggestion of propulsive forward motion.

As for the face on the software package, it belonged to a Haitian immigrant who was working at Saks Fifth Avenue in Beverly Hills when Les Crane and his Software Toolworks co-founder Joe Abrams stepped up to her perfume counter to buy a gift. Renée L’Espérance — the name “rivals Mavis Beacon’s in memorability and grandeur,” wrote Mashable’s Natasha Piñon in 2021 — made an immediate impression, which Joe Abrams recalled for Vice in 2015:

Abrams described Renee L’Esperance as a “stunning Haitian woman,” with “three-inch fingernails.” Crane instantly wanted to put her face on the box for his typing software. They got to talking, and despite the concerns Abrams voiced (“She’s never been near a keyboard!”), they soon made a deal. Abrams told us they paid L’Esperance a flat fee, bought her a conservative outfit that befitted a typist, and rented a business square in Century City on a Sunday, in order to take the cover photo. As for her long fingernails, Crane said “Don’t worry. We won’t show her hands,” according to Abrams.

The flat fee was $500 (about $1,385 in 2024 dollars).

Renée L’Espérance’s grand and memorable name tells a vivid story: Renée’s literal meaning is “reborn,” while L’Espérance means “the hope.” But although it’s pleasant to imagine that the Mavis Beacon gig gave Ms. L’Espérance a hopeful new life in this land of opportunity, nothing of the kind occurred. The $500 fee led to no residuals or future photo shoots; in the typing program “Mavis” spoke, but not in L’Espérance’s voice. In subsequent iterations of the software L’Espérance would be replaced by a succession of Mavises, all of them Black but none as influential as she was. L’Espérance herself soon disappeared, possibly moving back to Haiti; she has left no digital footprints, and the makers of Seeking Mavis Beacon were repeatedly frustrated in their efforts to make contact with her.

Still, as Seeking Mavis Beacon makes abundantly clear, this particular typing-teacher avatar did more than sell a product. There had been other Black corporate mascots — Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben — but they were subservient figures with racist backstories. “Mavis Beacon” was something new: a competent professional woman in a position of authority. The color of her skin was both irrelevant and hugely significant. No wonder her legacy continues to shine.

The creators of “Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing” were three white “guys from the Bronx,” as they called themselves. The guy in charge of idea generation and marketing was Les Crane, a former radio and TV host whose fourth wife was Tina Louise (“Ginger” on “Gilligan’s Island”).

This is an excellent example of the Mandela Effect: a false memory shared by a group of people.

This phenomenon of collective false memory is so fascinating. I had not heard of this documentary but it sounds so weirdly up my alley! Thanks for putting it in my radar.

Sometimes I remember the wonderful episode of Dick Van Dyke when the cast sang "Alan Brady, Alan Brady" (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VKHByjZhFR8), and it plays in my head for a while. Maybe now I'll mix it up with "Mavis Beacon, Mavis Beacon," which will sound at least as good.