By appointment only

At Saks Fifth Avenue's San Francisco store, shoppers no longer can come and go as they please. What does that portend for the future of retail?

This newsletter may exceed your email limits. To read all of it, click on the headline to view it in your browser or jump over to the Substack app.

When Saks Fifth Avenue opened its San Francisco store in 1952, it joined a vibrant downtown retail landscape. Almost all of Saks’s department-store neighbors were local or regional businesses of long standing: City of Paris, The White House, Roos-Atkins, The Emporium, I. Magnin, Joseph Magnin. Saks — like Macy’s, which had opened in 1945 a few blocks away — was an East Coast import, the “Fifth Avenue” in its name a nod to its New York provenance.1

Except for Macy’s, all of those other stores have vanished in the last seven decades, leaving their lovely buildings behind and largely vacant. (Also gone: Seattle-based Nordstrom, which closed its Market Street location in August 2023.) Macy’s will soon join the ranks of the departed: In February the company announced that it would be closing its huge Union Square store as soon as it could find a buyer for the real estate. (That still hasn’t happened.)

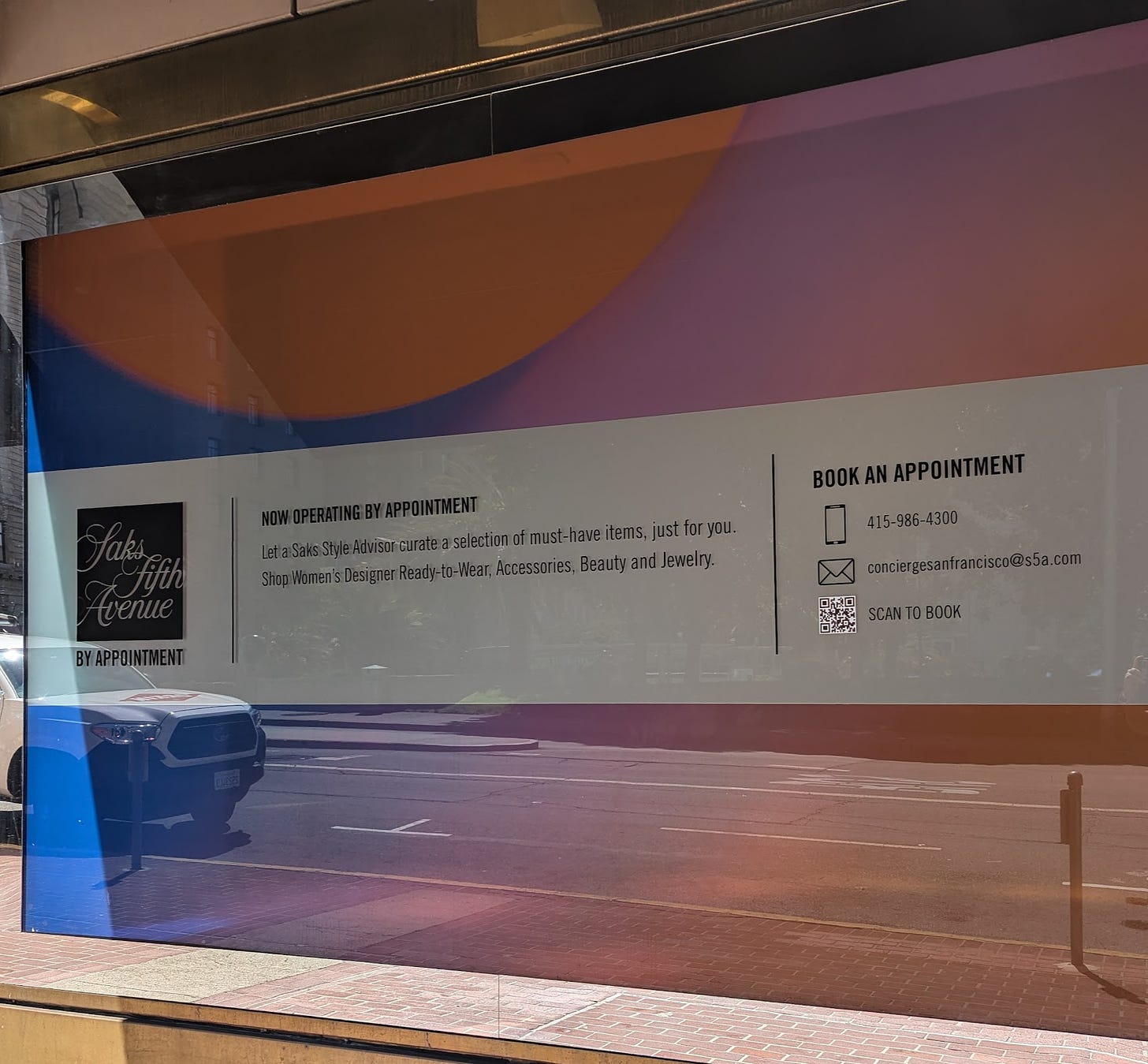

As for Saks, it’s in the middle of a $2.65 billion acquisition of Dallas-based luxury competitor Neiman Marcus. But that news didn’t prepare me for the the recent announcement that Saks’s San Francisco store would be switching to an appointment-only policy beginning August 28, and would no longer be open at all on Sundays and Mondays.

I had a hard time imagining what it would be like to have to beg for admission to a department store, even a fancy one like Saks. No more ducking inside to escape the rain or enjoy the air conditioning or take advantage of a nice ladies’ room? Participants in my Substack Chat were similarly puzzled. Was the decision prompted by “shrinkage” (aka shoplifting)? Was Saks looking to slash employee headcount in anticipation of the merger with Neiman Marcus? Was the appointment-only policy an attempt to inject some cachet into in-person shopping — a glamorous alternative to the solitary click-click-click of e-commerce?

I had to see for myself. And so earlier this month I made an appointment of my own — the website requires a minimum of three days’ advance notice — to venture into the brave new world of retail gatekeeping.

Okay, it isn’t an entirely new world. Saks had already converted its stores in Napa Valley and Palo Alto to “Fifth Avenue Clubs,” also open by appointment only and with a limited range of services and merchandise. And other luxury-retail establishments around San Francisco’s Union Square had been gradually fortifying their perimeters since the doomy days of 2020. At the Vince boutique on Geary Street the doors are permanently locked; to gain access you ring a bell and hope a sales associate will respond. And at the grand Neiman Marcus store on Stockton Street the first person you’re likely to encounter when you swing through the revolving doors is an imposingly tall, impressively beefy, and very conspicuously armed security guard.

Nor is this an entirely new world for me. My first job, in high school and intermittently throughout college, was at one of Los Angeles’s homegrown retail titans, The Broadway. My mother and I regularly made pilgrimages to the downtown Bullock’s and I. Magnin for the spectacular month-end sales, when hordes of hoi polloi like us would surge through the doors at precisely 10 a.m. and snap up the choice goods, now deeply discounted, that were normally accessible only to L.A.’s moneyed crowd. I later worked in editorial departments at Banana Republic and TravelSmith, and wrote copy for many other retail clients (including one that specialized in cloth diapers — I contain multitudes). And I’ve written about retail branding: See, for example, my February 2024 newsletter about the Stonestown Galleria.

To prepare for my shopping appointment on Friday the 13th of September I read as much as I could about Saks. There was surprisingly little to read. Saks isn’t known as a retail innovator; for that, look to Wanamaker’s in Philadelphia — the first department store to use price tags — and Lord & Taylor in New York, America’s first department store (founded in 1826) and the first retail establishment to hire a woman (Dorothy Shaver) as its president. It isn’t famous for outrageous “fantasy gifts,” like Neiman Marcus’s Noah’s Ark (1970 Christmas catalog: $588,247). It doesn’t have a Thanksgiving Day parade (that’s Macy’s), it isn’t known for extraordinary service (that’s Nordstrom), and it most certainly didn’t have a bargain basement (that was Filene’s, in Boston), although it did launch a chain of outlet stores, Saks Off Fifth, in 1990.2

Saks’s most newsworthy business move took place in 2007, when, as a PR stunt, it obtained a postal ZIP code — 10022-SHOE — for its New York store’s huge shoe salon.

The Saks brand may be best summed up by fashion historian Nancy MacDonell in her new book Empresses of Seventh Avenue. In the mid-20th century, writes MacDonell, Saks was known for being “snooty and hushed, the purlieu of wealthy matrons and their debutante daughters. Here, all was luxe, calme et volupté.” The reference is to Baudelaire’s “L’invitation au voyage”: “There, all is order and beauty / Luxury, peace, and pleasure.”

I am neither a wealthy matron nor a debutante daughter. Would I find “luxury, peace, and pleasure” in a docent-led tour of Saks San Francisco?

When I arrived at Saks at the appointed hour I waited in an anteroom while a a formidable looking hostess (a maîtresse d’hôtel?), her face a crack-resistant veneer of maquillage, checked off names in a big book. Behind her, sheer curtains created a wafting barrier, and beyong them was a “land of desire,” as the pioneering American department store owner John Wanamaker once called consumer capitalism. The hostess paired me with a “style advisor,” Cece, who was also assiduously made up and who greeted me cheerfully and escorted me onto the sales floor, where a dozen or so other shoppers, almost all of them women, were embarking on their own semi-private tours under the watchful eyes of their own style advisors.

This was a very different Saks than I remembered from the pre-pandemic years, when I had last shopped there. For starters, it had contracted. The top three floors of the five-story building have been shut down, leaving only the ground floor (expensive shoes, expensive bags, a few spendy cosmetics and fragrance brands) and the second floor (women’s designer clothing). The men’s department: gone. Children’s wear: gone. (Saks was once a prime destination for upscale layettes.) No lingerie. No jewelry not classified as “fine.” No restaurant. And no brand not deemed “luxury,” although I did manage to find a few pieces from up-and-coming Israeli American designer Nili Lotan, including a pair of $375 casual cotton pants, a price point that in context I was beginning to think of as “affordable.”3

The rest of the merchandise was, shall we say, out of my league.

Cece and I took the escalator to the second floor, which may as well have been the 102nd: It was that out of reach.

There was a single markdown rack with surprisingly conspicuous 70%-off signage.

Cece was a good-natured and chatty companion. “Pretend like I’m not here!” she told me when we got started. That was a relief: I had worried that she would hover at my elbow and follow me into the dressing room where, for the record, I tried on three pairs of pants and bought none.

Unlike Cece’s ensemble, the store’s ambient soundtrack was lulling, even trancelike. Cece and I took our leisurely time circumnavigating the floor, which was segmented into designer-brand niches: Carolina Herrera, Akris Punto, Dries van Noten, Ralph Lauren, Toteme, Issey Miyake, Valentino.

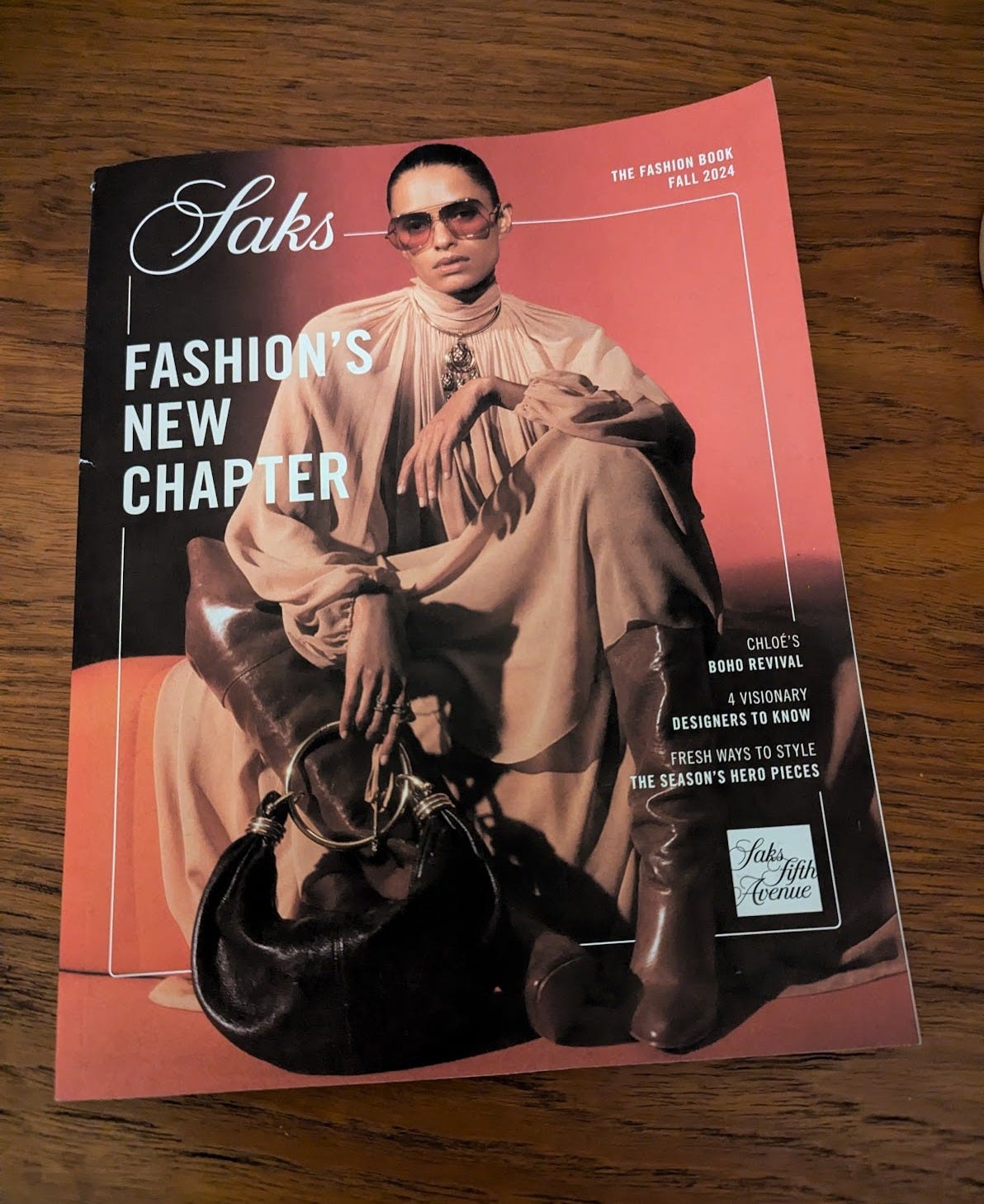

Multiple copies of a 60-page fall fashion catalog were strewn around the sales floor. Its pages includs many brands and styles not available in the physical store — L’Agence, Sam Edelman, Cynthia Rowley, even workwear stalwart Carhartt — as well as several pages of menswear.

The catalog had been designed, I deduced, to drive traffic not to the physical, appointment-only store but to the saksfifthavenue.com website.

Cece didn’t do a lot of style advising — she’d probably sized me up as budget-challenged — except to point out a Kilian fragrance preferred by the singer Rihanna and to tell me that “nobody carries big totes anymore — it’s all baby bags.” She also let me know that if I spent $700 that day I’d qualify for a $100 gift card. (The signs all around the sales floor imparted the same information.) This equates to a “circular” 14 percent discount: The savings can be applied only to more Saks merchandise.

I asked Cece — who told me she’d worked at this Saks store for nine years, mostly in the shoe department — whether the appointment-only policy was a temporary measure. She assured me it was not. As tactfully as I could, I inquired whether the store had had a shoplifting problem similar to, say, the one reported at Macy’s. Oh no, she assured me. Instead, she said rather vaguely, it was all about the impending merger with Neiman Marcus. (Maybe appointment-only is a last hurrah before a complete shutdown?) I asked whether appointment-only had been successful. “It’s only been a couple of weeks,” was Cece’s diplomatic response.

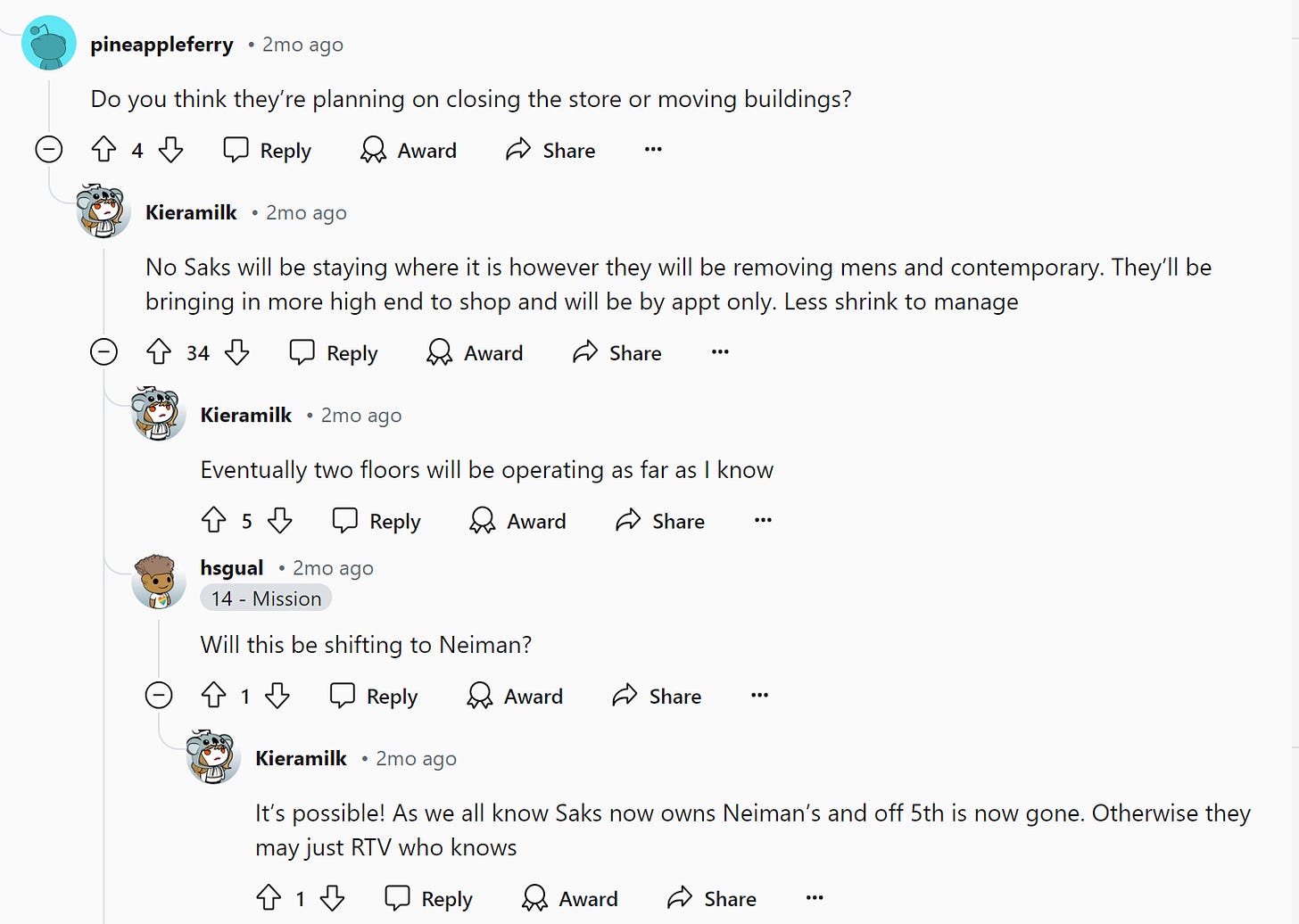

I got a different picture when I read a Reddit thread about Saks San Francisco. “I’m part of the beauty crew and boy was it a devastating day to say the least,” wrote “kieramilk” in July, after layoffs had been announced:

(“Shrink” = shoplifting and other types of theft. RTV = “return to vendor.”)

I left Saks San Francisco empty-handed but with my head full of thoughts. Although my little adventure had been interesting, I missed the high-low contrast of other department stores, where I could at least get a bite to eat if the clothing quest failed. The Saks experience reminded me of the brick-and-mortar stores operated by the resale site TheRealReal: On the website a shopper can find a range of “pre-loved” items at a range of prices; in the stores, which have small footprints, only high-end designer merchandise is on display. Is this a sustainable model for a department store with much more real estate and the added hurdle of an appointment requirement?

My guess is that it is not sustainable: that it’s a stopgap and an appetizer for the real meal, which is e-commerce. A glance at the Saks website appears to confirm my suspicion. Here’s what the About Us page currently says:

Job Opportunities

Join our fast-paced team as we build Saks Fifth Avenue into the finest retail presence on the Web, where style and personalized service are always a priority. Saks Fifth Avenue is always looking for talented, capable people. Saks creates rewarding career opportunities for all of our associates and recognizes them for meeting performance goals. Our growth and plans for the future offer unlimited challenges and responsibilities for talented individuals with management potential. To learn more about careers with Saks Fifth Avenue, click on the link below.

Emphasis added. The future, Saks is telling us, isn’t appointment-only: it’s online-only.

My styling advice? Make an appointment to tour Saks Union Square while you still can. It may be your last chance to experience real live in-person shopping in one of the last remaining shrines to luxe, calme et volupté.

The original Saks, founded by erstwhile street peddler Andrew Saks, a son of German Jewish immigrants, opened not on Fifth Avenue but on Washington, D.C.’s F Street, in 1867. The original Saks sold only men’s clothing; the flagship New York store didn’t open until 1924.

The Saks Off Fifth on San Francisco’s Market Street closed permanently in 2023.

I bought a couple of Nili Lotan pieces in 2021, when the designer did a collaboration with Target. I spent less than $60 on each item, and one of them was a fully lined trench coat. That was a very good collab.

Saks used to have the best men’s fashions in SF. Good tailors. Great luxury brand sweaters that went on sale at huge discounts. The pandemic ruined it. Salespeople who were helpful and knew what they were talking about. If you befriended them they could always find affordable stuff for you. During the pandemic and after It became a designer’s reject closet. Versace’s trash room.

Saks hasn’t even had a customer service department for several years. They don’t have a chance in hell of this new policy succeeding. Thanks for posting your experience

Nancy, you are the queen of retail rabbit-holes. I enjoy your pieces about stores and shopping centers, even though I seldom think about such things anymore. I was going to say that I couldn't imagine shopping with a "guide," but I just remembered that my most recent offline purchase was a pair of nice black shoes (for a wedding) in a geezer "slip-in" style by the high-end designers at Sketchers. I bought them at Dillard's, one of the few remaining department stores (with JC Penney and Target) in this area. I was helped by a guy who was working the shoe department by himself (the men's side, at least), and clearly had been for a long time. (It was the opposite of the "Best Buy" electronics experience, where your salesclerk's last job might have been flogging pots and pans.)

This guy took one look at me and my Crocs, and realized that my left foot was a size larger than my right. I love my Sketchers.