The only feature in the Sunday New York Times Style section that I read without fail is the advice column called “Social Q’s,” in which the very patient Philip Galanes answers questions about relationships, money, and the intersection of the two. The topics are usually present-day-ish (one of my favorites: “Who Gets the Cloned Dog in the Breakup?”), so I was more than a little surprised to see the decidedly un-modern word cad in the lead headline of the September 1 column:

You can read the full question, and Galanes’s reply, here (gift link).1 But I’m less interested in the dilemma — which strikes me as what another advice columnist, Dan Savage, would call a DTMFA situation — than in that amusing, antiquated word cad. It rang a little bell in my head that summoned a late-20th-century memory: not merely of a cad, but of what may have been the original cyber-cad.

I promise I will get to the cyber-cad story in a minute.

First, though, I owe you a little backstory about the root word cad, which turns out to be interesting in its own right.2

Cad has had a number of meanings since it first appeared in English around 1730 as a truncation of cadet, which had been borrowed from French. (It meant “little chief.”) A cadet could be a military student officer, whereas a cad always meant something else: originally a servant; later, in English student slang, what we Americans would call a townie. It also could mean “an assistant to the driver of a horse-drawn coach.” (Caddie, as in “golf-course schlepper,” also derives from cadet.) The implication, according to Green’s Dictionary of Slang, is that “such a figure could not be ‘a gentleman’.” (Thank you,

!)From “not a gentleman” cad ended up, by the 1820s, with its contemporary sense of “a person lacking the finer feelings”— or more precisely (to quote the OED) “a man who acts with deliberate disregard for another person’s rights or feelings, or who behaves dishonestly or dishonourably, esp. towards women; a philanderer or womanizer.”

The Oxford American Writer’s Thesaurus dismisses cad as “dated” and refers the reader to bastard (sense 2). There we find a rogue’s gallery of synonyms, including, well, rogue, as well as scoundrel, villain, rascal, weasel, snake, miscreant, good-for-nothing, reprobate, scalawag, jerk, lowlife, creep, sleazeball, swine, dog, nogoodnik, SOB, scumbag, hound, ratfink, knave, varlet, and blackguard.

It’s a colorful and comprehensive list — I’ve omitted a few — but it doesn’t include a word often seen in tandem with cad. I refer, of course, to bounder.

A bounder is similar to a cad, but there are distinctions. Both terms originated in England; bounder is a few decades younger (circa 1875). Green’s Dictionary of Slang says a bounder is a person (generally a man, I assume) who is “considered socially unacceptable or ill-mannered”; other sources suggest that a bounder “bounds” over social barriers.

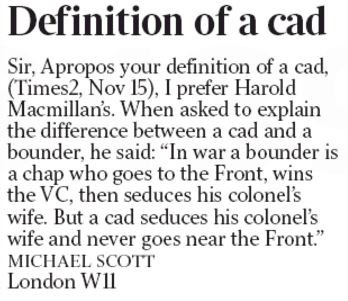

Harold Macmillan, prime minister of the UK from 1957 to 1963, may have had the most picturesque definition:

Speaking of seduction, here’s one more discussion of bounder vs. cad before I bound away: Back in February 2004, Washington Monthly political blogger Kevin Drum expressed puzzlement that a person (in this case, the gifted but incorrigibly creepy American architect Stanford White) could be labeled “a bounder and a cad.” What was the difference? Drum devoted the following day’s post to the “torrent” of reader response, including a note that “the phrase was often used by Bugs Bunny, usually addressed to Elmer Fudd on occasions when Bugs was in drag.” (I’m sorry to report I was unable to dig up a single example of the wascally wabbit uttering “bounder and cad.”)

Which brings us at last to the tale of the cyber-cad.

In the early 1990s, when monitors were monochrome and we connected to the World Wide Web via dialup modem, I was briefly a member of The WELL, one of the original online communities. (It’s still going strong!) One summer day in 1993 my friend and fellow WELLbeing3 J. phoned — on a landline, natch — to tell me about a shocking turn of events. Several members of the Women on The WELL (WOW) “conference,” or subgroup, had identified a fox in the henhouse: a cyber-cad. Yes, that was the word she used.4 The fellow, whose real name no one knew, had been courting multiple women online, then dumping them.

This may sound tame today, post-#MeToo, but trust me: It was a more innocent time. The internet was a Purely Good Thing, destined to unite the world in peace, love, and emoticons. We knew nothing back then of Nigerian princes or catfishing schemes. Elon Musk, wrecker of Twitter and so much else, was still an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania.

L’affaire cyber-cad sent shockwaves through The WELL that reverberated regionally, then nationally, and even internationally. On July 10, 1993, the Washington Post published John Schwartz’s 2,000-word story under the splendid headline “On-line Lothario’s Antics Prompt Debate on Cyber-Age Ethics.”5

“It started simply, as complicated stories often do,” Schwartz’s story began:

Two women were comparing notes late last month on their love lives. Not unusual, except perhaps for the fact that they began their chat in cyberspace. That is, they were communicating through computers and modems on a California-based service called the WELL.

It didn’t take long for the two women to realize that their hearts had been broken by the same man — a man who romanced them via electronic mail and by telephone, swore them to secrecy about their relationship, and even flew across the country to visit one of them in Sausalito, Calif. (He asked her to pay half of his plane ticket.) They began to discuss the matter with others . . . and found that he hadn’t just been two-timing them; he had been three- or four-timing them, at least.

The man had hidden his true identity from the women, who referred to him as “Mr. X” or “the Cyber-Scam Artist.” One woman, “Reva,” cautioned other women that “this is not normal courtship behavior.” No, Mr. X had “acted deceitfully and hurtfully, in a calculated, systematic way.”

Schwartz filled in the context for readers unacquainted with this newfangled form of communication:

Similar, if less spectacular, dramas are being played out in cyberspace across the nation. An estimated 15 million people have access to the Internet — the global network of computer networks developed mainly for the uses of academe, government and business. Several million people subscribe to consumer-oriented on-line services, from the thousands of small bulletin boards run by hobbyists to big commercial enterprises like Prodigy, CompuServe, America OnLine and GEnie. People use these services to get news and information, to trade stocks and even shop.

And even shop. Imagine that!

Schwartz managed to contact Mr. X, who predictably blamed “distortions and lies,” and later announced he would be leaving The WELL. The story ends with a quote from “Lizabeth,” one of the women who’d been involved with Mr. X. She expressed regret and delivered the money quote: “I don’t think he’s anything more than I’ve called him, which is a cyber-cad.”

(The whole article is wonderful and worth preserving in a time capsule. John Schwartz, by the way, went on to report climate stories for the New York Times; he now teaches journalism at the University of Texas at Austin.)

When Time magazine followed up on the story a week later it called the incident “Heartbreak in Cyberspace.” The reporter, Sophfronia Scott Gregory, elicited a little more from the still-anonymous Mr. X, who insisted that he was the victim here: “I feel my privacy was radically violated,” he protested.

(A linguistic side note: By 1993 cyberspace had been around for at least ten years. And cyber-, meaning “computer-related” and later “internet-related,” had been a productive combining form for almost three decades: The Raytheon Company had introduced its Cybertron computer in 1961, and the OED has citations for cyber kid and cyberman from 1971. Cyberpunk was coined in 1986. Along with cyber-cad, 1993 saw the invention of cybercash, cyberchondriac, and cybercommunity.)

The word cyber-cad does not appear in the Time story (or in the online OED), but it popped up across the globe in May 1994, when The Age (Melbourne, Australia) published the first installment of its “new column that observes happenings on the Internet.” The story, “ ‘Hot Chats’ Just Aren’t On, You Cybercad!”, referenced a Playboy article, “Orgasms Online,” that had retold the WELL tale. It included a quote from an annoyed WELL lady: “What I said, Mr I’m A Journalist And Get My Facts Straight Bigshot, is that I would share the name of the cybercad ... with people who asked in e-mail.” (I haven’t been able to locate the Playboy article, alas.) (UPDATE! The article was headlined “Lust Online” and it appeared in the April 1994 Playboy, but it’ll cost ya to view. Thanks a million, Carol Kino!)

In March 1999, The WELL’s executive director, Gail Williams, recalled the cyber-cad incident during a “live, moderated discussion” hosted by WashingtonPost.com. It had become “part of the folklore of the net,” she said:

[A] young unpublished novelist who was pleasant company in the WELL Writers conference and other hangouts started to put his writing talents to other uses. He became romantically involved with at least seven women on the WELL. At some point he started to discard some of his secret loves, and he made the mistake of unceremoniously dumping two girlfriends at the same time. . . . The outrage and the issues about secrecy and honesty were not new. They could have happened in a small town. But in cyberspace the community meeting which transpired was news. The “cad” was outed, but not by name. And he opted to leave the community. I went back and read a few of his posts in Writers... his problem was in writing a good ending. And I think that’s what got him!

The on- and offline media appear to have lost interest in cyber-cads after that, or maybe cyber-cads simply became too numerous to be newsworthy. I did find one late entry in the cyber-cad files: a December 2000 story in the Tampa Bay Times headlined “Cyber-cad Circulates His Date’s Lewd E-Mail.” Appearances to the contrary notwithstanding, the story wasn’t about a Florida Man; it was about a British couple, Claire and Brad, whose passionate evening went viral after Claire sent Brad a “racy e-mail” thanking him for “a great evening”:

Her boyfriend, now known to all the London tabloids as “Brad the Cad,” couldn’t resist forwarding the message to a few close mates. Naturally, they passed it along to others. Almost instantly, poor Claire became the Monica Lewinsky of the digital world, with her indiscreet remarks about her own sexual preferences forwarded around the world.

At least Claire’s confessions were merely text-based. These days, cyber-cads can do their dishonoring with willingly shared nude selfies. We have come so far, yet in many ways hardly progressed at all.

If you got the paper edition of the Times you’d have seen a cad-less headline: “Waving a Red Flag.”

I am aware that CAD is an acronym for computer-aided design. I’m limiting myself here to the lower-case cad.

That’s what we were actually called. The WELL was so cute.

When I reached J. over the weekend to ask about her memories of the incident, she told me she thought she’d made up the word. Which she may have done!

“Lothario” is “shorthand for an unscrupulous seducer of women.” Like “Romeo,” its source is play written by an English dramatist.

It won't surprise you to learn we are discussing this on the Well.

Come on back!

All fired-up to claim 'townie' for olde England, but of course you are spot-on and it takes well over a century for the Brits to catch on. They (well, Oxbridge since 18th cent.) have, see OED, always preferred Town (tout court). The usefully rhyming antonym was, naturally in the days when such garb was mandatory, ‘Gown’. Once upon a (medieval) time there were heavy-duty riots in which if heads didn't literally roll, corpses were undeniably created. A less lethal version can be found in ‘Cutherbert Bede’s’ The Adventures of Mr Verdant Green (1857). (And yes I had noticed: I too am doubly gullible: J(ay) Green.)