Why did Allbirds lay an egg?

The woolly sneakers were once the epitome of nerd chic. Did the brand's troubles start with its name?

Although I’ve never owned a pair of Allbirds sneakers — I’ve tried them on, but they disagreed with my fussy, high-arched feet — I’ve thought a lot about the brand since its launch on Kickstarter in 2016. During Peak Allbirds— between, say, 2018 and 2022 — the distinctively bland shoes with the merino-wool uppers were ubiquitous among the normcore set. In San Francisco, you couldn’t walk a block in certain neighborhoods without seeing a flock of Allbirds-clad techfolk. The brand had fans outside the Bay Area, too: President Obama wore Allbirds. So did Ben Affleck. Ditto Kristen Stewart.

The finance world took note: By the third quarter of 2019 Allbirds was a unicorn, valued at US$1.4 billion. The company went public in November 2021 with a market capitalization of $4 billion and an initial share price of $15. Shares zoomed to more than $535 later in the month.

It’s been almost all downhill since then. On March 11, Allbirds announced its worst earnings ever. On May 8, shares of Allbirds (BIRD on the Nasdaq) closed at $5.41.

What went wrong?

I’ve seen a few theories, and I’m going to propose one of my own.

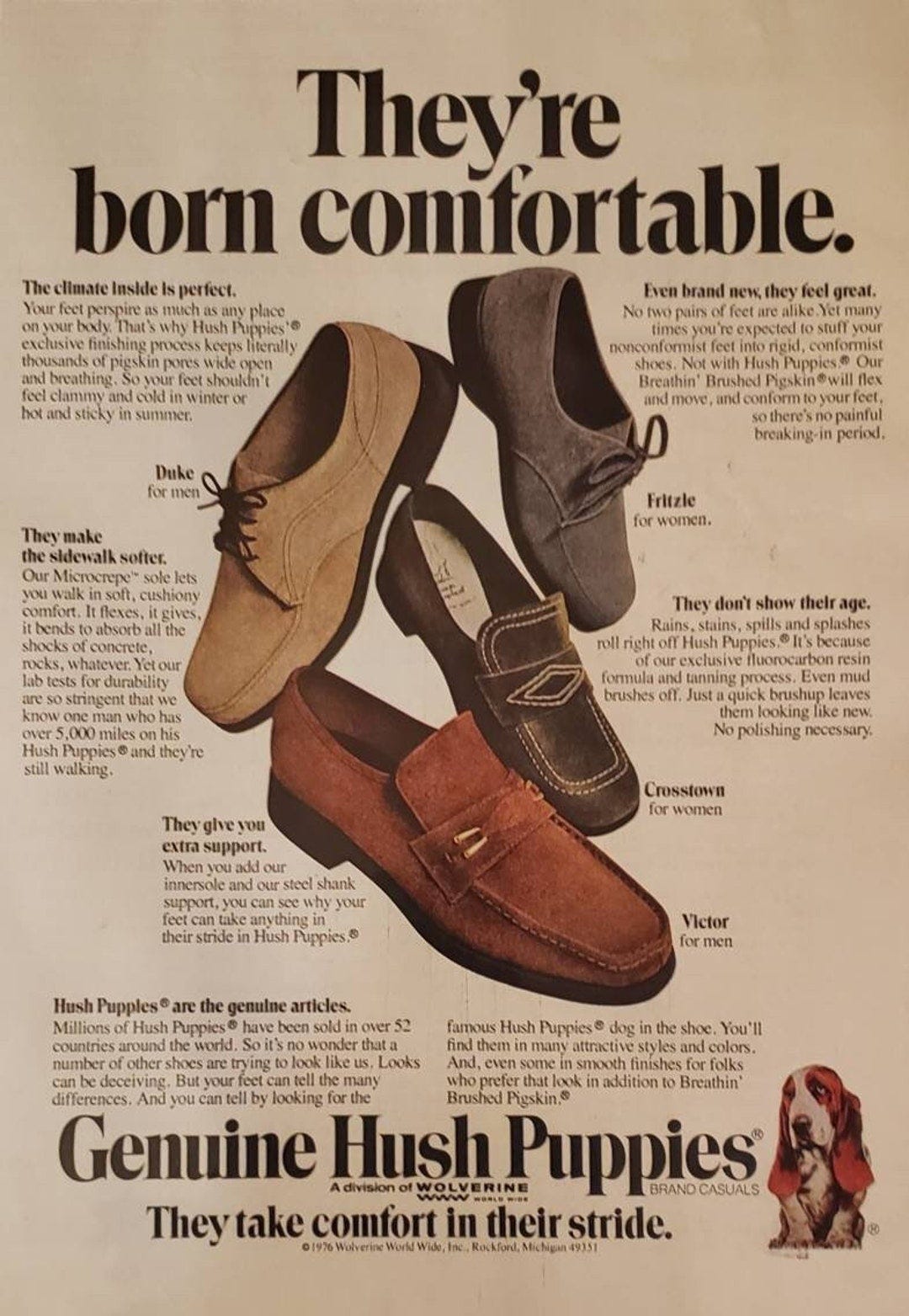

was pithily blunt in her March 13 Feed Me newsletter: “A reminder of how lack of sex appeal (along with mismanagement) can tank a business.”I don’t know enough about Allbirds’ management to comment. But I disagree about “lack of sex appeal.” Some conventionally “unsexy” shoes are hugely popular: See, for example, Birkenstock. See Ugg, whose name is either an abbreviation of “ugly” or a variation on “ugh.” See Crocs, the brand of foamy, hole-y (and, let’s face it, unsexy) clogs that launched in 2002 and in 2024 had a record year with $4.1 billion in revenue, representing 4 percent growth over 2023. See the example Malcolm Gladwell used in his first mega-best-seller, The Tipping Point: Hush Puppies, the quintessential normcore brand that had been all but dead in 1994 and became an unexpected fad a year later when some Manhattan hipsters and fashion designers decided to wear them.

Joe Hovde, whose

newsletter covers “business, technology, and psychology,” used Sundberg’s observation as a springboard for an April 13 essay, “What should Allbirds have done differently?” He concluded that yes, the company “shouldn’t have raised or spent money like a tech company” and had no need to be headquartered in high-rent San Francisco. But the main problem, as he saw it, was that Allbirds “did not take the time to properly tell its story” (emphasis Hovde’s):I am the exact demographic that should have known Allbirds’ story, and I only found out yesterday that the founder captained the New Zealand national soccer team, led them to their second World Cup, and started the company after making a minimalist shoe out of New Zealand wool and selling it to his teammates.

Instead of that story, the Allbirds story became the one about corporate growth from zero to unicorn. And when that’s the story you’re hearing — a story about numbers rather than about love or comfort or saving the planet — “like a virus the social organism tends to reject the brand.”

I’d take it one step further: the title of the Allbirds story was wrong from the start. And by title I mean the brand name.

Why, you may be wondering, is a shoe whose selling point is “merino wool uppers” calling itself “Allbirds”? There’s a reason, but you won’t find it on the Our Story page of the website. I found it instead in a 2018 CNBC story that profiled Tim Brown, the soccer-playing New Zealander who founded the company. The merino wool that goes into Allbirds sneakers’ uppers comes from New Zealand’s many, many sheep. And:

The name, Allbirds, is also a nod to New Zealand — it references the fact that the island-nation’s first settlers when they arrived in a land of “all birds,” Brown says.

That’s not a bad story, but I’m not convinced it’s an apt one. I’m straining to see the connection between birds and sheep (other than the fact that “flock” is the collective noun for both). And although Brown is a Kiwi, Allbirds has always been an American company. I’m skeptical that a proud New Zealand reference has much resonance with American consumers.

Allbirds strikes me as an OK placeholder name — a name that’s used internally until a superior candidate is thoroughly researched and developed. Name developer

wrote recently about the risks these “working names” pose. One risk is that your pet name, while meaningful to you, won’t communicate a clear value proposition to your audience. Founders tend to get attached to their own brainchildren and sometimes need to be (gently) persuaded to view the bigger picture.To see what Allbirds might have been, consider a rival “unsexy” shoe brand that has been racking up impressive sales — at higher price points than Allbirds’ — and attracting a passionately loyal following. And it’s doing it with a brand name that by rights should have belonged to Allbirds.

Hoka One One, known as Hoka, was founded in 2009 by two Frenchmen who wanted to develop a faster downhill-running shoe. The result was known as “the ugly shoe” because of its oversize outsole. Before long podiatrists were recommending Hoka sneakers to their patients, who appreciated the shoes’ stability and comfort.

And the name? It comes from a phrase in the Māori language that means “to fly.” (“To fly” is the company slogan.) Yes, Māori: those Polynesian early arrivals in New Zealand who noticed an absence of mammals.

I don’t know why two Frenchmen chose a Māori name for their brand, but they were smart to do so. As a name, Hoka has several advantages over Allbirds:

It’s easy to pronounce across multiple languages. The L and R sounds in the middle of Allbirds are notoriously difficult for speakers of many languages; “Allbirds” can be mis-heard as “Owlbirds” or “Auburns” or any number of other wrong choices.

You don’t have to know what Hoka means; it just sounds fun and upbeat. It functions as an empty vessel, fillable with multiple meanings. That makes it suitable for brand expansion and extension.

When you do know what Hoka means, it’s relevant and aspirational. You’re not walking or running — you’re flying!

It even bears a sneaky resemblance to that other big four-letter sportswear brand with a K in third position: Nike.

Hoka shoes have zero sex appeal, but unlike Allbirds they aren’t blandly unsexy. They wear their dorkiness as a point of pride and even accentuate it with wild color combinations. (See the Skyward X, for instance.)

Yes, there are other reasons for Allbirds’ troubles. Shoes made with woolen uppers tend to wear out more quickly than shoes made from tougher, longer-lasting synthetics; customers were disappointed. The brand has lost focus, expanding from everyday footwear into more technical categories such as running shoes and workout wear. Moreover, Allbirds seems unclear about who its target customer is. (Hovde’s observations about consultants’ role in this issue are fun to read.)

But I submit that the Allbirds name — and the absence of any tagline to support or clarify it — has been a liability from the start. Too bad Hoka got there first: That’s the authentically-rooted-in-New Zealand name that Allbirds should have claimed.

On LinkedIn, Mary La Coste brought up the All Blacks, New Zealand's national rugby team. Maybe Allbirds is meant to echo All Blacks? (I found no indication of a connection in any Allbirds messaging, though.)

Nancy, this is so good. Thanks. I like names that resist registering. You have to stop and think "what!" But "allbirds" slewed off into comprehension and you were obliged to fish it out again. And ended up thinking, "No, it can't be that" i.e., something to do with birds or all or especially all birds. But for me the big problem here was that they didn't "control the burn" which is to say they got a fantastic response from the early adopters and this converted the "charge" of the brand (to mix my metaphors, don't ask ME to brand anything) from positive to negative. We consumers choose a new brand because it's a little risky but when it ends up getting almost instant adoption in "our crowd" we looking like the most predictable dopes in the world. (I am pretty good at this all on my own, and don't need help from brands, thank you very much.) In the startup world that prizes originality and innovation, this was what do they call it exactly, oh, yeah, bad. So the best thing that could happen to a new brand was the worst, and it was up to the brand managers to control the burn by actually ratcheting demand back down and then only gradually scaling it back up. This is difficult and dangerous. But it is possible. Do I have an example. No, I don't have an example. Thanks again.